The auditor general recently commented in her audit report that Cape Town is exceeding every target for service delivery in townships. (David Harrison/M&G)

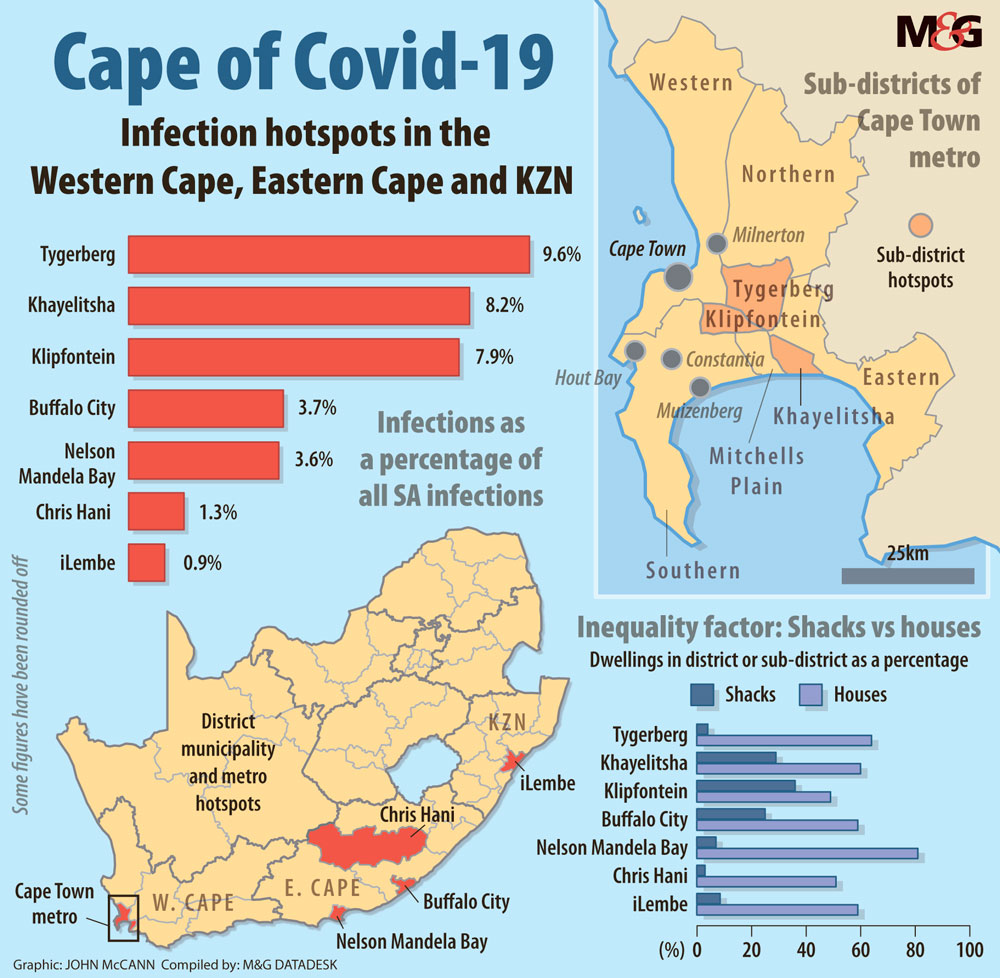

The Western Cape accounts for two thirds of South Africa’s Covid-19 cases — many in poor, crowded townships. It is the epicentre of the pandemic in the country and has recorded more infections than countries such as Ghana, Israel, Denmark and Poland.

By Wednesday, the province had 24 657 confirmed cases. The province with the next highest number of confirmed cases was Gauteng, followed by the Eastern Cape with 4 526 cases.

Much has been made of Covid-19 hitting anyone; the great leveller. But the Western Cape numbers show that the hardest-hit areas are densely populated and poverty stricken townships around Cape Town. These are areas where people cannot retreat behind the walls of a single home, work remotely or drive alone in a car to the shops.

These hotspots include Gugulethu, Nyanga, Langa, Khayelitsha, Philippi and Masiphumelele.

The Mail & Guardian analysed specific suburbs in four sub-districts with the highest number of cases. They include Tygerberg, where more than 3 500 people have tested positive, whereas the Khayelitsha and Klipfontein sub-districts combined have more than 6 000 cases, making up close to 25% of the province’s total.

These areas have a huge number of shack dwellings. For example, in Khayletsha’s Site C, about 46% of homes are shacks. Some 99% of the population is black, with an average annual income of about R15 000 and a 60% unemployment rate.

The figures are similar for townships such as Macassar and Mfuleni.

One of the townships that falls under the Klipfontein sub-district is Nyanga, where 98% of residents are black. Some 51% of the dwellings are shacks and residents, on average, earn less than R15 000 a year.

Covid spreading like fire

The concern about people squashed together in the midst of a pandemic that requires physical distancing was captured well in an April research paper by the Yale School of Medicine. Slum Health: arresting Covid-19 and improving well-being in urban informal settlements, noted that informal settlements in the Global South are the least well prepared for the pandemic.

They warned that “space constraints, violence and overcrowding in slums and tenements makes physical distancing and self-quarantine impractical, and the rapid spread of an infection highly likely”.

When the national lockdown started, local authorities scrambled to find shelter for people without homes, often with disastrous results. In Pretoria and Cape Town, people were packed into open-air stadiums as winter swirled. Food was scarce and, at first, so were proper safety measures.

The national human settlements department has also been talking up its intensified construction of homes to deal with the country’s backlog.

None of these initiatives substantially change the underlying social realities, where people left out of the formal economy are often forced to live close together, with families in single rooms and multiple families sharing a single yard.

The researchers argue that the pandemic will have an immediate and lasting effect on the lives and livelihoods of people in the informal settlements, as clean running water, water-borne sewerage, storm water drainage, waste collection and secure and adequate housing are in short supply or non-existent.

Closer to home, policy analyst and researcher at the University of the Witwatersrand, Hlengiwe Ndlovu, warned that a highly infectious disease such as Covid-19 could spread “like fire” through informal settlements: “Look at how shack fires happen: you light one fire, and the whole place burns down.”

Workplace clusters

Talking to the M&G, Western Cape Premier Alan Winde said the province has developed a data-led targeted hotspot strategy, which aims to change behaviour to slow the spread of the virus. He said all eight sub-districts in the City of Cape Town have recorded a growth in positive cases over the past four weeks.

“The initial growth has been linked with specific workplace clusters, from the third week of April. We saw clusters of infections occurring where people were still able to gather under lockdown like essential-service workplaces, such as supermarkets, police stations, hospitals and prisons. These people then went home to the communities they live in, which resulted in spread there.”

Winde said these clusters have seeded more than 790 positive cases to date and that the hotspot areas with the highest density of cases are being targeted to limit the ongoing spread of the virus.

He conceded that the Western Cape “has entrenched community transmission, which has resulted in our curve accelerating faster”.

Winde said that community screening continued and that the use of isolation and quarantine facilities, especially for those living in densely populated areas or in homes where this was not possible, were all tools which could help slow the spread of the disease.

But he argued that behavioural changes such as personal hygiene, physical distancing and the wearing of masks were all-important

The Covid-focus problem

At the core of the province’s health response will be several dedicated Covid hospitals around the Cape metro, including a facility at the Cape Town International Convention Centre that will accommodate more than 800 patients, as well as facilities in Khayelitsha and Brackenfell.

Some healthcare workers in the province have, however, warned that the focus on Covid-19 means other patients do not get treated.

Johannes Fagan, who heads up the Otolaryngology (head and neck) division at Groote Schuur Hospital and is a member of the University of Cape Town’s Health Sciences faculty told the M&G: “We need to avoid all our hospitals and doctors becoming ‘Covid hospitals’ and ‘Covid doctors’, to the exclusion of appropriately managing other diseases, perhaps with better prognosis.”

He added that: “This requires careful and considered allocation of scarce resources by priority setting across disciplines, regardless of Covid status.”

“Our concern is that the Covid crisis is being seen as a separate issue to our overall health care, but we feel it should be part of the spectrum of health care, it shouldn’t be put on a pedestal to manage differently.”

Fagan said elective surgery, such as hip replacements and ear surgery, must wait “but we have to treat our trauma patients, we have to treat our sepsis, our diabetics and our heart patients”.

The emphasis on Covid-19 means “these patients are going to fall through the cracks,” he warned.

Fagan, along with other senior medical professionals, published a letter in the South African Medical Journal late last month sharing the same concern.

“[We] have witnessed how the intense focus on Covid has created a backlog of patients with non-Covid diseases who are not able to access care. Many cancer diagnoses, and hence treatments, have been delayed, as have joint replacements and cataract surgery. Patients with diabetes, asthma and other chronic illnesses have missed appointments. Many are unable to access medications.”

In Wuhan, China, the solution was to put Covid-19 patients outside of the existing treatment system. Learning from fever clinics, the state created a system where people with possible symptoms were screened, tested and treated without going through the usual healthcare system.

Last week, the Western Cape government announced projections that the province would reach its peak of infections by July. Already there is strain on its public health sector, with intensive care unit beds reported to be at their maximum.

How it will work

The Western Cape department of health responded to the M&G by saying the province’s Covid-19 hospitals would be primarily staffed by doctors and nurses from the public sector, as well as other healthcare workers that will be recruited for the duration of the pandemic.

Department head Keith Cloete said the dedicated hospitals would be used for patients presenting with mild symptoms who required hospitalisation. These hospitals would be overseen by existing managers from within the system and would be staffed by general doctors and nurses who are currently being recruited.

Cloete denied that senior specialist doctors would be deployed: “Specialists will continue to work at tertiary hospitals. The more moderate and severe Covid-19 cases are being managed at tertiary hospitals.”

As a result, Cloete said: “This has an impact on the availability of critical care beds, which impacts on the ability of surgeons to operate on patients that would require critical care post-operatively. It is for this reason that all elective [non-urgent] surgical procedures have been postponed until the current wave of Covid-19 cases has subsided.”

Meanwhile, the Western Cape government confirmed this week that it was changing its testing protocol in the Cape Town metropole to only test high-risk vulnerable people for the virus. These include those over the age of 55, people who are admitted to hospital with Covid-19 symptoms and people with comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes and HIV.

This is after the National Health Laboratory Service said that a backlog of tests for the province had grown to 27 000.