Founders: Congress leaders Walter Rubusana Thomas and Saul Msane (back row) and Mtobi Mapikela, John Dube and Sol Plaatje in a photograph from 1914 (above).

The ANC has typically been led by intellectuals who articulated ideas that sought to transform South Africa. Instead of settling for what was, they reimagined the country.

For a liberation movement now 110 years old, perhaps it is unrealistic to have expected the party to remain permanently defined by intellectual curiosity. Could it be that the intellectual orientation of the movement was always bound to be subject to the ebb and flow of the organisation itself, suppressing and illuminating intellectualism at different times in its history?

Correct, but to a point. Societal structure determines both the possibility and boundaries, but agency or will is the ultimate catalyst.

Spurred by demands for a common society and equality, the ANC could only have been formed by the African elite. They were part of an integrated society, from the early 1800s, born and educated at mission stations. Both the lifestyle and Christian education buttressed their indigenous ethos of the sameness of humanity. However, missionaries and those who purported to be “friends of the natives” (also known as liberals) did not always live by their own teachings.

St. John’s African Methodist Episcopal Church. African priests broke away to form their own churches, including the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church.

St. John’s African Methodist Episcopal Church. African priests broke away to form their own churches, including the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church.

Their version of equality was a lopsided relationship, with them only in positions of authority. “Native” priests (in the nomenclature of the time), especially from the 1880s, were denied promotions to place them on par with their white counterparts. When the number of native voters threatened to surpass that of settlers, liberals, who had been recipients of native votes, withdrew support for the African franchise.

They joined Afrikaner politicians in their long battle to disenfranchise the “natives”. Income as a prerequisite for voting, for instance, was increased, leaving out a considerable number of African voters from the early 1890s. By the close of the 19th century, relations between the African elite and their former benefactors — liberals and missionaries — were increasingly competitive.

African priests broke away to form their own churches, including the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. The public leaders formed their newspaper in 1896, Izwi LaBantu, to articulate their demands independent of settlers. Africans were now breaking out of settler tutelage, even going overseas, from the 1890s to seek tertiary education. The US-based AME church was central in recruiting Africans for further education in the American diaspora. Charlotte Manye Maxeke was among the first of such recruits and became a fierce advocate of cross-continental relations among people of African descent.

The overseas experience encouraged the African elite even further to take independent initiatives. They were receptive to Booker T Washington and WEB Du Bois’s calls for self-improvement and political agitation. John Langalibalele Dube was inspired to form the Ohlange Institute high school. Mpilo Rubusana had a similar inspiration to form a university but faced serious competition from liberals who were determined to beat him to it.

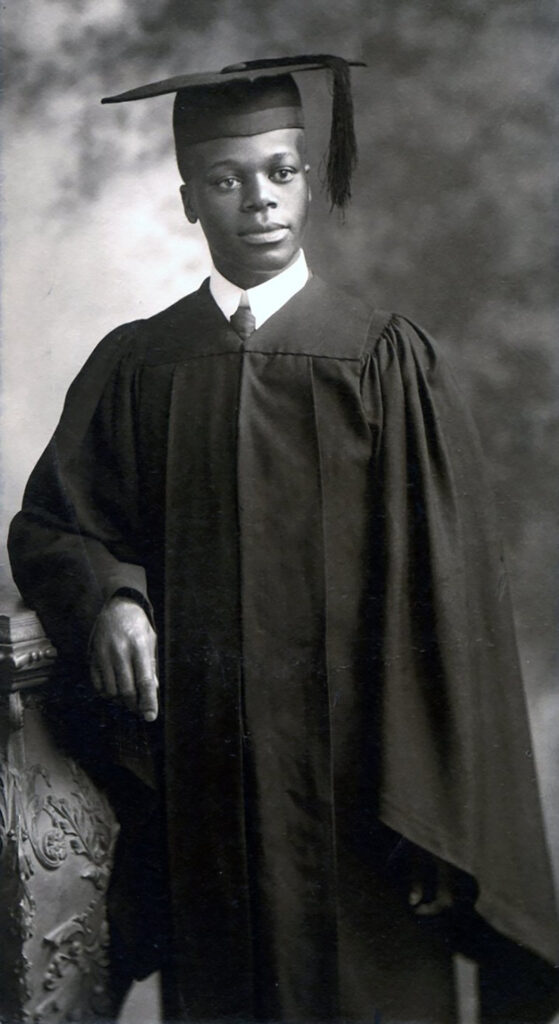

John Dube was the founding president of the SA Native National Congress, renamed the ANC in 1923.

John Dube was the founding president of the SA Native National Congress, renamed the ANC in 1923.Rubusana had contacted the Africanist-orientated AME church to set up the institution, which made officialdom fearful that his university would turn its students against the political establishment. Liberals would eventually succeed in setting up their own institution in 1916 — the South African Native College, later renamed Fort Hare University — intending to produce pliant students who would be submissive to South Africa’s racial hierarchy.

Settlers, however, did not have complete control over knowledge production. African leaders managed to assert total influence over their political instruments, both in terms of press media and organisationally.

Several African-owned newspapers sprung up from the early 1900s. These included Dube’s Ilanga and Sol Plaatje’s Tsala ea Becoana. They formed their own national political organisation, the African Native National Congress, in 1912 and excluded settlers.

By now, they had learned something that would become a common refrain in the black community: ungaz’ umthembe umlungu! The ANC was set up as a tool for political agitation. The newspapers spread the message.

To them, it was not just about agitation but also articulating ideas that conveyed the society they were striving towards. Political agitation was a battle of ideas, and they articulated those ideas, however unfashionable at the time. Some such ideas were equality and nonracialism. They assailed racist bigotry as an assault on humanity and rallied the rest of the world against the racist state.

With some of its founders educated abroad and a regular presence at pan-African congresses throughout the world, the ANC was a global movement at birth. Its global reach, however, was not enabled simply by its presence. It was also because of its intellectual leadership, combined with the eloquence and universality of their ideas. Solomon Plaatje, the first secretary general, took to writing books, including Native Life in South Africa, to document the brutality of the Union’s belief in racial supremacy.

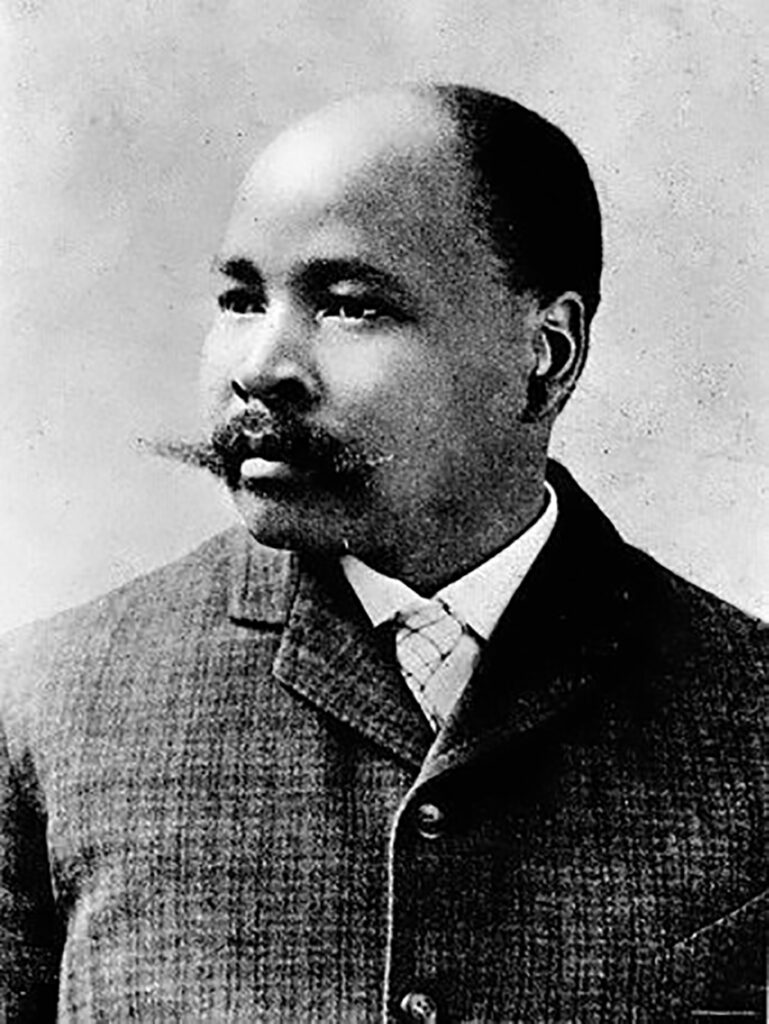

Mpilo Rubusana

Mpilo Rubusana The potency of ANC ideas, aided by the intellectual curiosity of African students, even changed Fort Hare University from an instrument of social control to a hotbed of African nationalism. The ANC Youth League was formed almost exclusively by Fort Hare graduates and the campus became one of its first branches. Influenced by the Youth League, students across the continent were inspired to form liberation movements in their countries and adopted the name African National Congress.

Armed with education, Youth League leaders added to the construction of the idea of South African nationhood. Industrialisation hadn’t become widespread, limiting contact among people of different ethnic groups. Common belonging could not be cultivated or ethnic prejudice broken through physical contact. Nationhood had to be imagined. History had to be recalled and interpreted to give it concreteness that lent credence to the idea of a nation.

Nationalist intellectuals spoke of a collective history of resistance that affirmed our common belonging and defined citizenship based on residence, not indigeneity, and around a particular set of ideas.

Their hybridity checked the dominance of the exclusivist, Afro-centric definition of citizenship. Nonracialism also paved the way for the adoption of Marxism as one of the analytical tools within the liberation movement.

And, so from the 1940s onwards, the liberation movement would both draw and be guided by multiple intellectual traditions. This legacy, both in practice and theoretical frameworks, would form the basis of the constitutional architecture underpinning the new South Africa.

Pixley ka Isaka Seme

Pixley ka Isaka SemeThe belief in nonracialism foreclosed any possibility of vengeance. Though fully aware that racism has a life of its own, ordinary folk were also alert that it could be manipulated to advance capitalist exploitation. Sometimes claims of black solidarity mask the accumulation of advantage by a clique. South Africa thus declared itself a “rainbow nation of God” with each of us being our “brother’s keeper”.

Pixley Seme’s historic call, made at Columbia University in 1906, for the regeneration of Africa served as an inspiration for Thabo Mbeki’s African renaissance. Both history and ideas provided inspiration for a new vision.

Intellectual curiosity ended once ANC leaders, cheered on by the South African Communist Party and union federation Cosatu, looked upon state control as an instrument for material accumulation. Engorgement has no use for ideas and mobilisation towards a vision but involves brute politics of exclusion and building numbers to create a winning majority. Absent any guiding idea, everything went in this frenzy, including corruption and bellicose rhetoric.

Now people feign surprise when voters vote more along racial and ethnic lines. Civic ties, spurred by collective aspirations, are loosening as individuals look toward their own for care. It is easy for the comfort that comes with power to kill inspiration. But it need not be that way. China’s Communist Party, which is effectively a nationalist movement, is proof of that.

The ANC needs to regain that intellectual curiosity to provide leadership to day-to-day activities. Without it, the party will simply revolve around the same spot, mistaking activity for progress.

Mcebisi Ndletyana is a professor of political science at the University of Johannesburg and co-author of a forthcoming book on the centenary history of Fort Hare University