Sixteen southern white rhinos have been moved from &Beyond Phinda Private Game Reserve in KwaZulu-Natal to Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

(Photo by Wolfgang Kaehler/LightRocket via Getty Images)

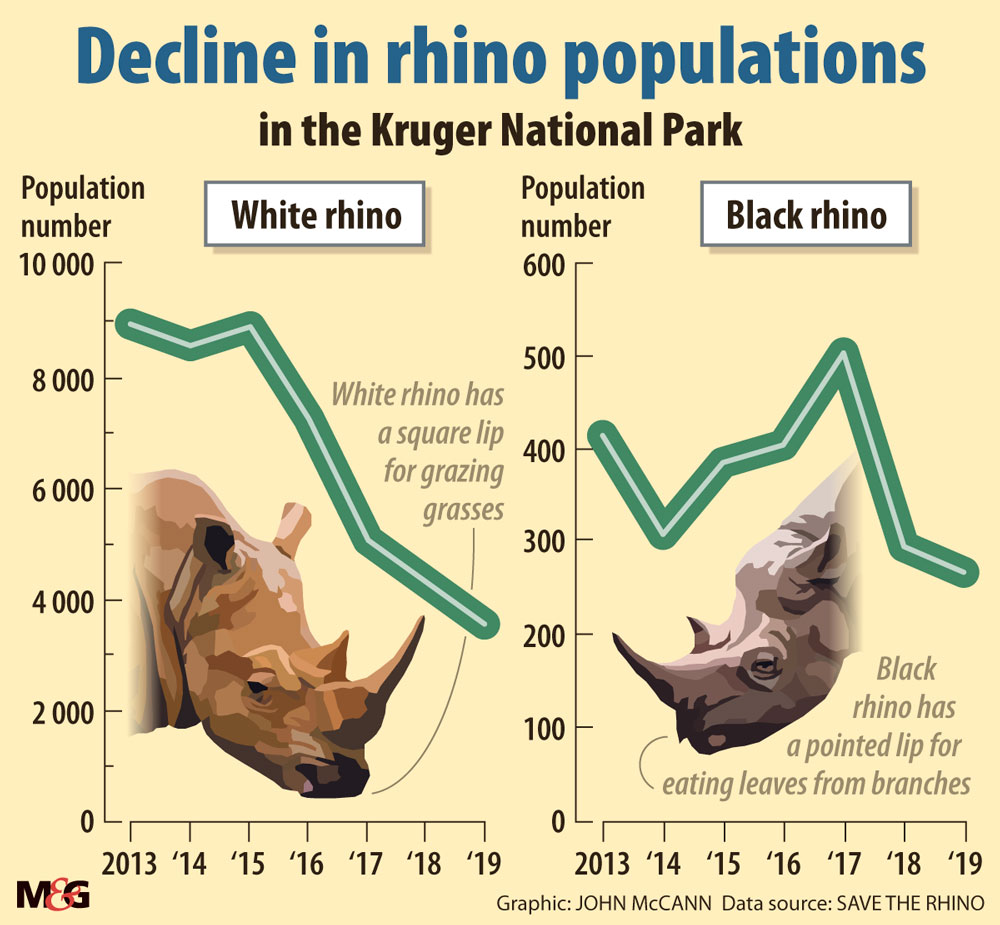

Rhino populations in the Kruger National Park have dropped by about 70% in the past decade because of the onslaught of poaching and prolonged drought. In its 2019-20 annual report, SANParks said that only about 3 549 white rhinos and 268 black rhinos remain in the Kruger.

The park has been hit by a “perfect storm”, said Mike Knight, the chairperson of the African rhino specialist group in the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s species survival commission.

“For the Kruger, it’s size and position plays against it when you are trying to protect species populations,” he said, citing the park’s long, porous border with Mozambique.

The 2015-16 drought, Knight said, also placed rhinos under duress and female rhinos couldn’t conceive or had lost their calves, “which hammered the population even more”.

In its annual report, SANParks said its latest population estimates show that births equal combined natural and poaching deaths for the first time in five years.

“This bodes well for future population growth,” it said.

The nonprofit Save the Rhino said although the Kruger continues to be home to the world’s largest rhino population, the latest population numbers are a “stark reminder” of their fragility. “We cannot afford to let this downward trend continue.”

Earlier this week, the department of environment, forestry, and fisheries said that 394 rhino were poached last year compared with 594 in 2019, marking the sixth year that rhino poaching had continued to decrease in South Africa.

The country’s lockdown restrictions contributed in part to the decrease, as did the role of rangers and security personnel who remained at their posts and the additional steps taken by the government, said Barbara Creecy, the minister of environment, forestry, and fisheries.

The environment department said poachers killing cows also ultimately kill dependent calves and cause future loss of calves — this effect equates to an additional five rhinos lost to the population per loss of one cow, now and in future. “Poaching also causes factors such as social disruption of black rhino societies. Cows then conceive less often.”

It said the discovery of bovine TB in the Kruger rhino population effectively halted the translocation of rhino to other safer areas.

“Droughts also continue to have lingering effects. During the 2015-16 drought, white rhinos died naturally at twice the normal rate. The cows also did not conceive and Kruger recorded half the birth rate a year after the drought. Two years after the drought, however, Kruger recorded high recruitment rates because many cows simultaneously gave birth in that year.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

“Most of those cows are now suckling calves and therefore not as many cows gave birth in 2020 compared to 2019. The gestation period for a rhino cow is 16 months and hence a rhino cow will only calf every 2.5 to three years,” the department added.

Knight said: “You’ve got to make sure you secure the parks, and at the same time you’ve got to give greater attention, as [the department] has been doing now, to chasing the middlemen, the moneybags, breaking the syndicates. Here we need greater cooperation between the private sector and [the department], and there needs to be greater cooperation between law enforcement agencies in South Africa and outside.”

The World Wildlife Fund for Nature South Africa said the rhino poaching reprise provided by the lockdown restrictions last year was a temporary pause “and that the pressure on our rhino populations, particularly in Kruger, remains very high”.