Sasol, South Africa’s second-biggest polluter behind Eskom, has committed to a net zero emissions target by 2050.

(Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

A former Sasol employee has endured “five years of hell” after blowing the whistle on how the petrochemical giant allegedly, through gross negligence, pumped hazardous chemicals into the Vaal River system because of broken chemical sewer valves at its Secunda operations.

Ian Erasmus, who worked as a senior process controller from 2005 until he was allegedly forced to resign last year, says it is “unquantifiable” what his disclosures over the unlawful disposal of the toxic chemicals vanadium, diethanolamine and potassium carbonate at the firm’s Benfield unit, have cost him.

The father of two has lost his only source of income, is on antidepressants, and his marriage has suffered irreparable harm from the stress of being unfairly discharged.

Victimised: Ian Erasmus says he reported a faulty valve in 2012 and 2015, then to Sasol’s ethics department and finally to the Human Rights Commission

Victimised: Ian Erasmus says he reported a faulty valve in 2012 and 2015, then to Sasol’s ethics department and finally to the Human Rights Commission

“To see your marriage dissolve right in front of you is horrible,” he says. “You fight, but it just slips through your fingers.”

In February last year, Erasmus was hospitalised after suffering multiple mental breakdowns. He has regular breakdowns because the case is hanging over his life.

“The South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) and the department of environmental affairs (now the department of environment, forestry and fisheries) did nothing for two years since I testified and gave affidavits … It is absolutely terrifying to be a whistleblower in Sasol, to have to fight for years against repeated retaliation without any help whatsoever.”

‘Threats to keep quiet’

Erasmus tells how he has suffered victimisation, severe prejudicial treatment, harassment and threats to keep quiet.

“I was told by managers that I should be fired. My grievances were ignored. I was subjected to multiple suspensions, contrived dismissal attempts and was even assaulted by one manager at work and again in the Secunda Mall.”

This, he says, was for “speaking up when no one else had the courage to” about the unlawful waste disposal activities allegedly perpetrated by a handful of employees at the Benfield unit.

In February 2019, he testified about this at the SAHRC’s inquiry into the Vaal River’s pollution. Three months later, he was suspended.

But it was seven years earlier, in January 2012, when he first noticed that a valve at the unit could not close.

A polluted water stream in Secunda.

A polluted water stream in Secunda.

“A water hose was open on one of the pumps on Benfield phase one. But the phase 1 chemical sewer was completely empty. So I went to phase 1 Benfield chemical drain valve and tried to close it. But it was clear it was broken and did not close.”

He reported it to his foreman, put in an order to have the valve repaired — and forgot about it. But in 2015, Erasmus noticed the same valve was still broken. He alerted his managers and put in another order for repair, but that, too, was rejected.

“I started putting in regular requests to have the valve repaired, but there was no action to repair these valves, so I reported it to the Sasol ethics department.”

‘Treated like a criminal’

When there was still no action for years, he “decided to do the right thing” according to Sasol’s codes and procedures on whistleblowing by disclosing the information to the then department of environmental affairs.

Even though two senior Sasol environmental managers were aware of the broken valves, nothing happened, he claims.

Erasmus made another protected disclosure to the SAHRC “because this Benfield waste can and probably has ended up in the Vaal River unchecked for years”.

The manager who allegedly assaulted him was legally responsible for fixing the waste disposal at the Benfield unit “and has the most to lose.” Instead, Erasmus claims Sasol reprimanded him for making a case against this manager and in his fifth disciplinary enquiry, he was charged for harassing the manager.

He sent his suspension notice to the SAHRC and the department, but “they could not help me get Sasol to do the right thing”.

“I was labelled a potential terrorist and saboteur in that notice … before being removed from the Sasol Secunda site like a criminal,” he says.

Erasmus provided “undeniable evidence” to the SAHRC and the department that the broken valves were replaced and “covered up” immediately after his testimony.

“They flushed and replaced the entire cooling water system inventory in the two weeks after I testified at SAHRC. It was an almost black-brown colour, and magically it changed to a light brown, like river water, within two weeks.”

He says he handed over evidence to the department and the SAHRC that massive amounts of vanadium were present in the firm’s western API dams in 2017 and 2018 for extended periods with Sasol’s own analyses of the API dam water.

API dams are the facility’s catchment dams for stormwater as well as for hydrocarbon (oils) polluted water. The water in these dams is recycled for use in Sasol’s process water.

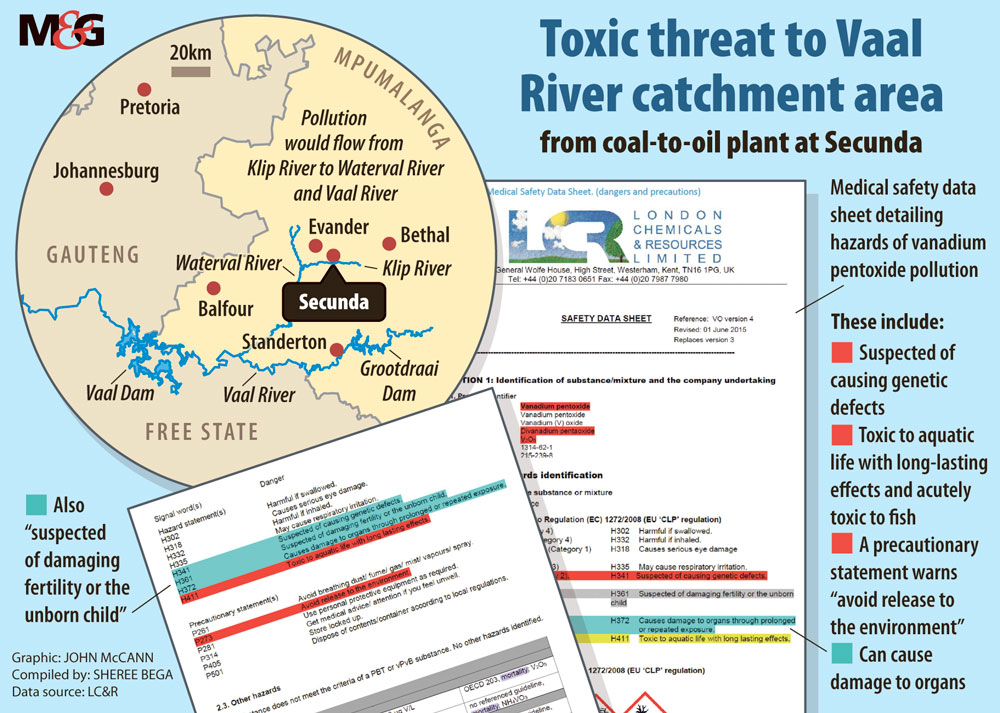

Vanadium exposure is suspected of causing genetic defects, damage to organs through prolonged and repeated exposure and is toxic to aquatic life.

Yet, Erasmus says, the alleged perpetrators are still “safe and sound” in their jobs.

“Not one of my colleagues wants to speak up because they saw how I was just taken out … I lost all my friends at my work. They are reluctant to even speak with me in a social setting.”

Expensive lawyers

Erasmus had to borrow money to hire a lawyer to try to get his job back, while Sasol, he says, “hired million-rand lawyers”.

He was offered a lump sum to resign in 2019, which he declined.

“Sasol management made it very clear that if I do not resign, then I will be fired, but whatever I do, they will get me out of the company one way or another.”

Since 2015, he has been in front of five disciplinary inquiries, each with charges “designed to dismiss” him, where he used a stack of documents “literally 1m high” to defend himself.

By the fifth disciplinary inquiry, Erasmus realised he could never win against a management team “who don’t even follow their own policies and codes regarding anti-retaliation, ethics and their own whistleblower policy”.

In July last year, he was forced to sign a non-disclosure agreement and resign or face dismissal on bogus charges, he says.

“I never thought I would lose my job for just doing my job. Speaking up in Sasol has destroyed my life.”

‘We are investigating’

Last month, the SAHRC released its long-awaited report on the Vaal River system’s sewage contamination, which did not include industrial sources of pollution.

“We are planning to investigate the industrial pollution separately, based on the testimony of the Sasol whistleblower,” says Mateenah Hunter-Parsonage, a senior legal consultant at the commission’s Gauteng office.

“We may decide to do it as an individual complaint and not as a full-on inquiry.”

Eric Mokonyama, the commission’s Mpumalanga provincial manager, says his office will lead the investigation and will be sending Sasol an allegation letter imminently.

Criminal case against Sasol

Albi Modise, the spokesperson for the department of environment, forestry and fisheries, says it is in the process of a criminal investigation into the information that was provided by Erasmus to the SAHRC.

“The SAHRC has indicated to the department that it is also investigating Mr Erasmus’ testimony into the industrial pollution of the Vaal River,” Modise says.

The case has been registered on the environmental management inspectorate registration system.

Modise explains this is a requirement in terms of the standard operating procedure between the South African Police Services and the environmental authorities.

After Erasmus’ testimony to the SAHRC, a verification inspection was undertaken at the facility in April 2019.

“At about the same time, Mr Erasmus was approached for his affidavit in May 2019, which included a considerable amount of technical information.”

The findings were released to the department’s criminal investigator in October 2019.

Modise says a detailed analysis of Erasmus’ technical information, together with the site verification findings, was then undertaken by the criminal investigator during the early part of 2020.

“A subsequent need for further investigation was identified before the docket could be handed over to the director of public prosecutions (DPP).”

It was determined that additional information was required to ensure that all the relevant details on this matter were placed before the DPP.

“This aspect of the investigation was delayed due to the national lockdown that was imposed to curb the spread of Covid-19. The minister [Barbara Creecy] has conveyed to the department that delays in the matter are unacceptable and the matter must be prioritised for completion in the first quarter of the 2021-2022 financial year.”

No protection

Samson Mokoena of the Vaal Environmental Justice Alliance says the SAHRC must investigate industries polluting the Vaal for decades without consequence. “There is no protection for whistleblowers in South Africa, especially on the environmental side,” Mokoena says.

He cites the case of Dr Pieter van Eeden, a toxicologist at the-then Iscor, now ArcelorMittal, who blew the whistle on the company’s unsound environmental practices in 2001 and leaked pollution reports. Van Eeden, who was suspended — and then reinstated — left Iscor after only 19 months.

“I think whistleblowers are punished for doing good in a system that says it needs them but does not act that way,” says Dr Victor Munnik, a research associate at the society, work and politics institute at Wits University, who wrote about Van Eeden in his 2012 PhD thesis.

Erasmus is on a WhatsApp group with ten other whistleblowers, led by former SAA group treasurer Cynthia Stimpel.

Other members include Eskom’s former head of legal and compliance Suzanne Daniels; Altu Sadie, an Ecobank whistleblower and Devoshum Moodley-Veera, who blew the whistle on misrepresented audit reports.

“They are all financial people speaking up on Gupta stuff et cetera. Me, from an environmental side, I’m the odd one in the group.”

Erasmus says the Protected Disclosures Act is an empty promise with “absolutely no support” from the government. While the National Environmental Management Act states no whistleblower will be retaliated against, the environment department “did absolutely nothing to help me”.

The Companies Act could not protect him as a whistleblower, nor could the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration.

“The fact is that these are only pieces of paper, and in the end, the only option you have is to apply to the Labour Court. No normal employee has that kind of money, and the companies know and count on it. Even if you do win your case, you are not guaranteed a reinstatement.”

Petrol company issues a flat denial of claims

Sasol spokesperson Matebello Motloung referred the Mail & Guardian to the statement it issued on 21 February 2019 following Erasmus’ testimony to the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC).

Sasol categorically refuted Erasmus’s claims that the company had polluted and continued to pollute the Vaal River or any other water source.

The allegation that vanadium and potassium carbonate were being dumped by its Synfuels operations into the Vaal River system was factually incorrect.

“Sasol Synfuels operations in Secunda utilises these chemicals in its Benfield operation units as agents to protect the metal of the equipment, as well as to absorb carbon dioxide. Due to the potentially harmful impact these chemicals can have on people and the environment, these chemicals are managed in accordance with the various requirements governing these hazardous substances.

“Various precautionary measures are utilised to manage any possible exposure or leakage as dictated by applicable environmental and occupational health and safety legal requirements,” it reads.

Sasol participated extensively in the SAHRC inquiry into the Vaal River’s pollution from sewage and the upper Vaal industrialisation.

“Sasol’s participation included an oral representation at the hearing of 20 November 2018, a submission of a written response on 30 November 2018, as well as accommodating a visit of the SAHRC and two SABC representatives at our Secunda operations on 5 February 2019,” the statement reads.

The SAHRC, Motloung says, concluded its inquiry into the matter and issued its final report on 17 February 2021. “It contains no findings against Sasol whatsoever. Therefore, we regard the matter as concluded.”

Erasmus, Motloung said, is no longer in Sasol’s employ after he and Sasol agreed to what she called a mutual separation in July 2020.

“Sasol promotes a culture in which all stakeholders, especially employees and personnel, are encouraged to speak up about unethical, illegal, or undesirable conduct involving Sasol and those engaged with it, without fear of retaliation or reprisal.

“We do not tolerate harassment, bullying or abusive behaviour that creates a humiliating, hostile or offensive work environment). This is underpinned by our whistleblower policy and our code of conduct, which we consistently apply, including in this matter.”

Motloung says Sasol is a key stakeholder to the sustainability of the integrated Vaal River system and “it is in all our interest in the long term sustainability of this vital resource to the regions. We remain committed to assist the SAHRC as far as reasonably possible and will fully cooperate in any subsequent inquiries once we have been formally notified.”