People’s hero: A mural depicting Amílcar Cabral who was the foremost leader of the struggle for the independence of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde from Portugal. (Photo by GUIZIOU Franck / hemis.fr / hemis.fr / Hemis via AFP)

In January 1973 there was a significant political awakening in Durban. At the same time, a generative political life came to an end in Conakry, Guinea. On 9 January workers at the Coronation Brick and Tile factory in Durban struck, beginning what came to be known as the Durban strikes.

On 20 January the same year, Amílcar Cabral, the revolutionary Pan-Africanist, was assassinated in Conakry.

The Durban strikes opened the way to rebuild the black trade union movement, which became a formidable political force by the 1980s. They also began the process of building democratic forms of popular politics that would move out of the factories and, by the 1980s, bring millions of people into often self-organised forms of resistance that centred the agency of the oppressed.

Cabral, the foremost leader of the struggle for the independence of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde from Portugal, is often primarily remembered as a military strategist and theorist, and as a leader who moved in the same circles as people like Frantz Fanon, Patrice Lumumba and Kwame Nkrumah.

As a military leader in the Pan-African movement for national liberation, he is a figure closer to Umkhonto weSizwe intellectuals like Chris Hani or Jabulani “Mzala” Nxumalo than the worker leaders who emerged after the Durban strikes, people like Jabu Ndlovu and Moses Mayekiso.

But contemporaneous events in Southern and West Africa were connected in many ways. The Durban strikes were retrospectively understood as part of a wider Durban moment that included the emergence of the Black Consciousness Movement with the formation of the South African Students’ Organisation (Saso) in 1968.

Steve Biko and the charismatic academic Rick Turner — the leading personalities in the Durban moment — opened new vistas of thought that enabled new forms of practice. They were both banned in 1973, after the initial Durban strikes.

The following year the Young Turks in the Black Consciousness Movement in the city organised a rally in support of the Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (Frelimo), the national liberation movement in Mozambique.

An electric moment

The rally was a direct challenge to the state. Its organisers — among them Saths Cooper, Muntu Myeza, Aubrey Mokoape and Strini Moodley — were arrested, tried, and eventually jailed, putting an end to the Durban Moment. In 1976 the Soweto Uprising shifted the locus of struggle to Johannesburg. Biko was murdered in 1977 and Turner was assassinated in 1978.

But, for an electric moment, the armed struggle against Portuguese colonialism seemed tantalising close to Durban. There were other kinds of connections outward too. One was to the Algerian struggle. At some point after 1973 — there is no public record of the exact dates — Josie Fanon, Frantz Fanon’s widow, visited Durban, staying at Turner’s home, presumably under some sort of cover.

In the wake of the Durban strikes, Paulo Freire, the radical Brazilian intellectual, became a theoretical lodestar for many university-educated radicals willing to take a reflective approach to the question of praxis.

As I have noted in this publication before, Biko had introduced Freire’s thought to Durban, where it was taken up by Turner and other university-trained intellectuals. Freire’s most famous book Pedagogy of the Oppressed, first published in Spanish in 1968 and then in English in 1970, drew inspiration from many sources, including African anti-colonial struggles.

Fanon’s last book, The Damned of the Earth, published shortly after his death in 1961, is often reduced to its opening remarks about anti-colonial violence. But the book is profoundly concerned with the question of praxis, of uniting theory and action in struggle.

It takes ideas very seriously. For Fanon, productive encounters between university-trained intellectuals and oppressed people were critical for building popular democratic power. He affirmed the imperative for the development of “a mutual current of enlightenment and enrichment” between protagonists from different social locations.

Fanon insisted that political education should not “treat the masses as children” and described this approach as “criminal superficiality”. Freire, who swiftly grasped Fanon’s thinking, wrote: “Leaders who do not act dialogically, but insist on imposing their decisions, do not organise the people — they manipulate them. They do not liberate, nor are they liberated: they oppress.” In 1987 he recalled that “I was writing Pedagogy of the Oppressed, and the book was almost finished when I read Fanon. I had to rewrite the book.”

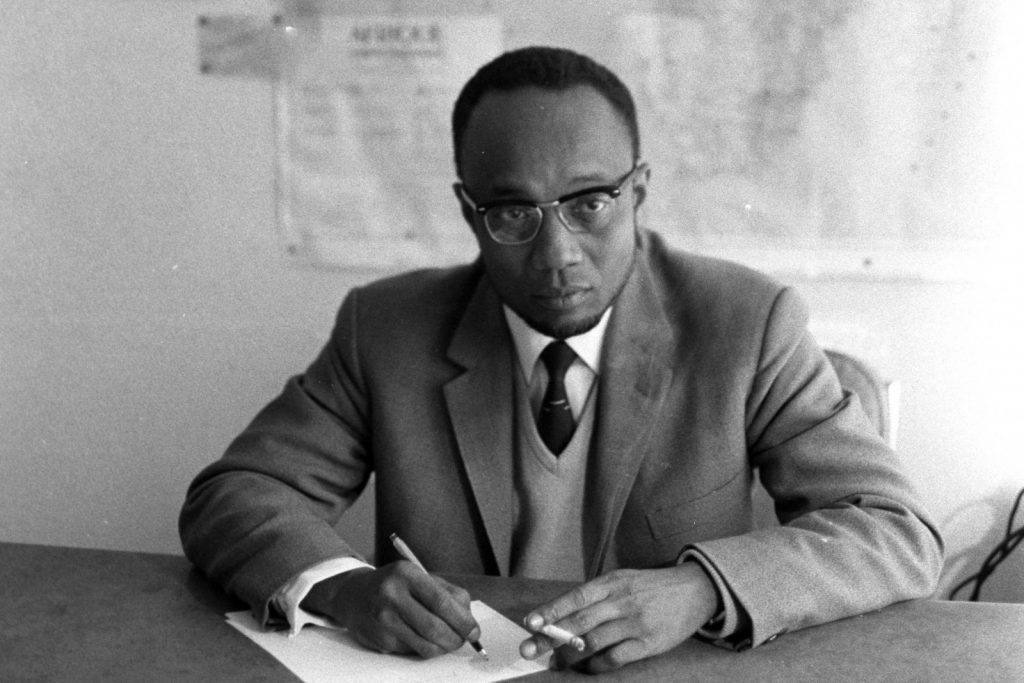

Revolutionary: Amílcar Cabral wrote that education was “the fundamental basis that underpins the work of the emancipation of every human being”. (Photograph by Ben Martin/Getty Images)

Revolutionary: Amílcar Cabral wrote that education was “the fundamental basis that underpins the work of the emancipation of every human being”. (Photograph by Ben Martin/Getty Images)

The common wind

Cabral’s thought was also in the air, floating in what William Wordsworth, writing about Toussaint L’Ouverture — the leader of the revolution against slavery in Haiti — called “the breathing of the common wind” that carries the aspiration for emancipation across the planet.

Like Fanon, Cabral was fundamentally committed to the idea of praxis grounded in mutuality, to careful and empathetic listening and “the use of a direct language that all can understand” as essential to the development of revolutionary reason and practice.

He understood the collaborative development of thought in the struggle to be fundamental and insisted that it should be “the consciousness of a man that guides the gun, and not the gun that guides his consciousness”. His first biographer, Basil Davidson, described him as “a supreme educator in the widest sense of the word”.

Cabral wrote that education was “the fundamental basis that underpins the work of the emancipation of every human being”. The movement led by Cabral, the African Party for the Independence of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde (PAIGC), took education as central to its work. Beginning in 1963 schools and libraries were established in the liberated zones, territories reclaimed via armed struggle.

After the April 1974 Carnation Revolution in Portugal the independence of Guinea-Bissau, which had been declared in September the previous year after 10 years of war, was accepted and in September 1975 Freire arrived in the country having been invited to collaborate with the new state on popular education projects. In Pedagogy in Process: The Letters to Guinea-Bissau, first published in 1978, he demonstrates a keen interest in Cabral’s thought and practices, and the practices of the PAIGC.

He gives a sense of the political meeting constituted in emancipatory commitment and held in the shade of a tree that resonates with Fanon’s earlier formulation of such meetings as “privileged occasions given to a human being to listen and to speak. At each meeting … the eye discovers a landscape more and more in keeping with human dignity”.

Freire’s ideas retained their significance in South Africa through the tumult of the 1980s. They are still, although at a lesser scale, engaged in new forms and sites of struggle. They are central to the Frantz Fanon School in the eKhenana Commune, a land occupation in Durban affiliated to Abahlali baseMjondolo.

Freire’s ideas remain a vital force elsewhere in the world, such as the Florestan Fernandes National School outside São Paulo. The school is run by the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra, the Brazilian movement of the landless. Fittingly, given Freire’s own internationalism, the movement of people and ideas between these and similar political education projects enables ongoing and mutual learning across borders.

There are still direct lines of connection between the Durban moment and contemporary organisation and struggle in the city. Rubin Philip, who was elected as deputy president to Biko in Saso in 1972 and banned the following year, was later able to meet and engage Freire in person. He has remained extraordinarily committed to grassroots struggle throughout the post-apartheid period.

David Hemson, who was banned in the same year, and played an important role in the development of the labour movement in Durban before, during and immediately after the 1973 strikes, also remains engaged.

Freire continues to be read. Popular democratic power is still being constructed, although at a much smaller scale than in the 1970s and 1980s and under conditions of severe repression. Three leaders in the eKhenana Commune were assassinated last year.

But, in the main, and with significant exceptions, the record of the left intelligentsia after apartheid is, in terms of effectively participating in building movements, one of failure. All too often the will to dominate — to, in Freire’s terms, “manipulate” — has precluded the sort of commitment to reciprocity and mutual learning that animated the thought and practice of people like Fanon, Cabral and Freire and enabled movement building.

The situation has been compounded by an insufficiently critical attitude to the ubiquity of the NGO form and its relentless substitution for the organisation of the oppressed in the name of “civil society”.

But the lessons forged in struggle from Durban to Algeria and Guinea-Bissau still float in the common wind.

Richard Pithouse is editor-at-large at Inkani Books, which recently published a new collection of Amilcar Cabral’s writing, Tell No Lies, Claim No Easy Victories.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.