Desperate: An image of a family home during the Irish famine from 1845 to 1850, in which more than a million people died. (Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty Images)

Those who think the British Empire was a benevolent, light-spreading enterprise — and an industry of historical apologists has sprung up in recent years — should read the accounts of Ireland’s “Great Hunger”.

“The Almighty indeed sent the potato blight, but England caused the famine,” famously remarked Irish nationalist writer John Mitchel.

Lasting from 1845 to 1850 the Drochsheol (Irish for “hard times”, always capitalised) killed at least a million people through starvation and disease and precipitated the exodus of over a million more across the Atlantic and the Irish Sea.

In a cataclysm rivalling Joseph Stalin’s mass starvation of Ukrainians, Irish numbers shrank from a projected nine million to 6.5 million.

The Hunger scarred the national psyche and quickened the drive for independence from Britain.

Together with the emigration and famine museums in the capital, Dublin, memorials stand in 14 counties, many near the unmarked graves of famine victims.

It reminds us that imperialism is built on ideas of racial hierarchy and generally entails violent coercion.

And it underlines the horrors of ideological cruelty — in this case entrenched anti-Catholic prejudice, the providential belief that all events are divinely ordained and the Victorian ruling-class worship of private enterprise and laissez-faire.

Conditions favoured mass hunger. After the forced marriage of the Act of Union — a British security measure imposed during the Napoleonic Wars — the Irish were subservient to Westminster.

Earlier, in the Cromwellian “settlement” of the 1650s, the overwhelmingly Catholic peasantry was driven into the bogs and mountains of the south and west that were unsuited to grain farming.

When the blight fungus arrived from America in 1845, two-thirds were living on potatoes, with adults eating up to 7kg a day.

Irish rentier capitalism was no spur to good farming. Under tenure “at will”, with the ever-present threat of summary eviction, tenants lived in a state of chronic insecurity, sullen subjection and fear of change.

Landlords, many of them absentee, used agents to collect rents that were up to double those of Britain. Large tracts were let to “land sharks” who subdivided plots into ever-shrinking parcels for profit — 40% were smaller than five acres. All improvements belonged to the landlord.

In charge of the British famine response was the central relief coordinator, Sir Charles Trevelyan, a flint-hearted Cornishman who believed private trade was “the chief resource for the subsistence of the people” and later welcomed The Hunger as “the direct stroke of an all-wise and all-merciful providence”.

Trevelyan, the niggardly chancellor Charles Wood and the Whig prime minister John Russell firmly believed that, left unfettered by the state, the market would deliver.

Government food purchases and subsidised handouts were taboo, with direct relief confined to the utterly destitute.

The emphasis was on “natural solutions” and sturdy private initiative. The treasury’s relief funding from 1845 to 1850 was primarily intended for price stabilisation, rather than feeding, and for public works including roads “from nowhere to nowhere” and piers that were quickly swept away by Atlantic storms.

A key delusion of colonialism lies in its determined, and generally ignorant, efforts to force alien systems on the colonised. “The English knew as little about Ireland as they did about West Africa,” remarked a commissary official.

The role of private trade was exalted as paramount — despite the lack of shops and distribution networks in Ireland’s most neglected and famine-afflicted counties.

In the The Great Hunger, historian Cecil Woodham-Smith observes that the peasants were so unused to money that they often pawned it or “stuck it in the thatch”.

Woodham-Smith relates that the most bitterly felt grievance was the refusal, in contrast with previous famines, to suspend food exports from Ireland to Britain. Trevelyan insisted that “perfect free trade is the right course”.

Gaunt scarecrows, the Irish were forced to watch ships guarded by cannons, cavalrymen and foot soldiers process down the River Fergus in County Clare laden with barley, wheat, butter and meal, prompting Irish MP William Smith O’Brien’s bitter complaint that instead of edible supplies Britain sent guns.

After the partial dearth of 1845 came two years of total crop failure, when potato plants “as black as tar” produced tubers that collapsed in a foul-smelling pulp.

“I confess myself unmanned by the intensity and extent of the suffering I witnessed, especially among women and little children,” wrote Captain Wynne of Ennis.

“Crowds of them … scattered like a flock of famished crows, devouring raw turnips.

“Mothers half-naked, shivering in the snow and sleet, uttered exclamations of despair while their children screamed with hunger.”

Claiming “trade had been paralysed by government food purchases”, Trevelyan decreed that free issues of Indian cornmeal supplied by the previous administration of Sir Robert Peel must end.

In 1847 he and Wood also shut down the works programme. Instead of “outdoor relief”, the able-bodied destitute would be fed in workhouses under the Irish Poor Law, funded at higher rates to be extracted from local property owners.

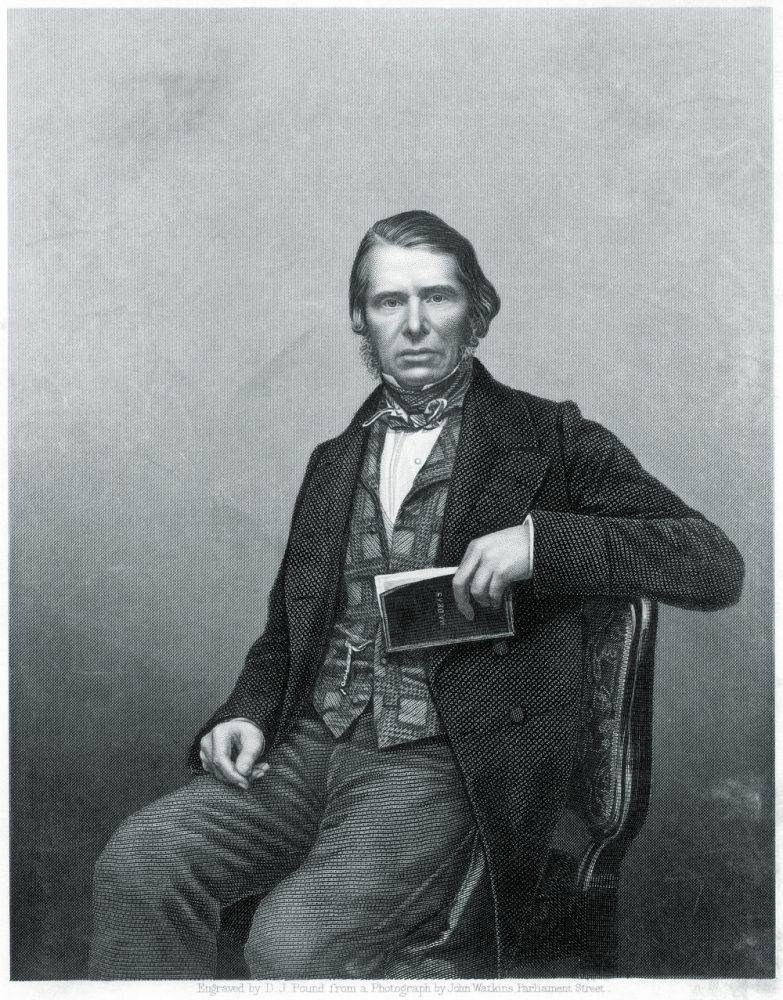

Britain’s central famine relief coordinator Sir Charles Trevelyan in an engraving by DJ Pound

Britain’s central famine relief coordinator Sir Charles Trevelyan in an engraving by DJ Pound

The trouble with this self-serving dodge was that most workhouses were chronically debt-ridden and over-subscribed — more than 200 000 destitute paupers were crammed into institutions that were built for half that number.

Trevelyan must have known that only eight Poor Law unions had more than £3 600 in hand; while the debts of the remaining 122 stood at £250 000.

The hardest-hit districts in Connaught and Munster, “swarming with squatters and miserable wretches living in sod or furze huts and bog holes”, were often vast, with few solvent ratepayers.

“No one in many miles could have contributed a shilling,” objected one official.

But the British persisted in the canard that by turning the screws, the required rates — estimated at £42 000 a week — could be squeezed from the debt-crushed Irish landed class and their penniless tenantry.

Warships were moored offshore, together with companies of soldiers and hussars, to back up rent collection.

“Arrest, remand … I should not be squeamish,” Wood urged.

Some large landowners used the famine to consolidate their holdings by evicting destitute rent defaulters. Britain’s foreign secretary Lord Palmerston, for example, evicted 174 tenants from his Sligo estates who then arrived almost naked in Canada.

In March 1847 came the coup de grace — lice-borne typhus (the “black fever”) and “relapsing fever” (the “yellow fever”) began to sweep the filthy, ragged, starving populace, who were packed together in public works projects and workhouse “fever sheds”.

Woodham-Smith writes that in County Mayo in the destitute west, there was one dispensary for 366 000 inhabitants. In Cork, 102 boys lay in a ward with 24 beds.

Where hastily erected sheds could not hold them, some of the sick lay uncovered in the streets.

Hunger, disease, evictions and the dreaded workhouse fuelled the gathering torrent of emigration to the New World and to the west coast of Britain, much of it in unseaworthy “coffin” ships.

At one point in 1847, 36 vessels were queuing at Grosse Isle in Canada’s St Lawrence River, all fever-tainted. Over five months, 300 000 Irish paupers landed in Liverpool.

Racial contempt for the Irish as idle, improvident and ungovernable permeated the policy outlook of Victorian England.

Together with the ruthless Highland clearances in Scotland, the Great Hunger exposed the hollowness of Union — the House of Commons would never have countenanced such hunger at home.

The £8 million disbursed by the treasury in relief over five years was a tenth of the British government outlay on the Crimean War. Critics pointed to the £20 million paid in compensation to former Caribbean slave owners.

Referring to the failed 1848 Young Ireland uprising against British rule, Trevelyan wrote that “the great evil we face is not … the famine, but the moral evil of the selfish, perverse and turbulent character of the people”.

Russell warned of “extreme” British anger over Ireland’s “mendicancy and ingratitude”. For Wood, its lack of natural harbours showed “the Almighty never intended [it] to be a great nation”.

As the famine dragged on without correcting itself through “natural solutions”, British indifference and even belief in its merits, as a remedy for Ireland’s “surplus population” and reliance on the potato, seemed to grow.

Theologian Benjamin Jowett reported overhearing a political economist remark that if the famine killed a million, “that would scarcely be enough to do much good”. Woodham-Smith identifies the speaker as government adviser Nassau Senior.

The Lord Lieutenant, Lord Clarendon, protested that no other European legislature would disregard the suffering in the west of Ireland “or coldly persist in a policy of extermination”.

No attempt was made to strengthen Irish farming through new crops and methods or to reform the tenure system. Trevelyan refused to pay for alternative seed.

The idea that racial inferiority and providence predetermined the Irish holocaust seems to have been accepted at the highest level.

In 1848, with the famine still raging, Charles Trevelyan was made Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath for his services. Later, he would be elevated to the rank of baronet.

Drew Forrest is a former Mail & Guardian deputy editor. He is on holiday in Ireland.