An opposition MP in Cape Town and a senior civil servant in Pretoria agreed on one thing this week – South Africa is not veering towards a police state, “we are already there”.

Call a politician or a civil servant on their cellphone these days and there is a sense of agitation on their part that the caller should know better. In some cases, there is even fear. That is because, in a climate of paranoia and intimidation, few in their right mind would openly talk on the phone.

Following a recent spate of incidents – so far dismissed as random acts of crime – several political observers have hinted that this may be the workings of state security, signs that its machinery is in full swing.

On the afternoon of Sunday March 20, robbers tied up a guard and made their way into a building in Parktown, Johannesburg, to steal seven computers from the Helen Suzman Foundation.

The building is owned by the cosmetics mogul, Reeva Forman, whose plush offices and those of two other tenants didn’t attract the attention of the robbers. It was just the foundation and it’s offices – on the top floor.

Perhaps coincidentally, the robbery happened days after the foundation filed court papers challenging the controversial appointment of Hawks head Major General Berning Ntlemeza, who had been chastised by a high court judge for lying under oath.

One senior government source said this week: “You may think all their documents are in the public domain, so what were they [the robbers] trying to achieve? Well, what about email trails? After all, someone is feeding the foundation with information.”

The apparent random hijacking of the former army chief Siphiwe Nyanda also grabbed headlines – authorities made special mention of the fact that he was hijacked while driving a Porsche Panamera.

Was this a message to the well-heeled general, one of several former Umkhonto weSizwe commanders who released an open letter calling for President Jacob Zuma to step down last month?

An incident involving Economic Freedom Fighters leader Julius Malema being pulled over by about a dozen Metro police officers in Sandton, Johannesburg, has been dismissed as a standard response because Malema was allegedly travelling in a blue-light vehicle.

But EFF spokesperson Mbuyiseni Ndlozi said there was no truth to these claims: “Even if that was the case, how can they justify such a forceful response, men storming out of their cars with rifles, deadly weapons?”

The EFF, he said, maintains that the incident was the first concrete case of an attempt to intimidate their commander in chief, adding that they have reliably been informed that this “will not be the last time”.

Then, last Friday night, forensic investigator Paul O’Sullivan, buckled up in seat 5A – seen with a glass of champagne in hand – was pulled off a London-bound SAA flight – days after threatening to expose several top cops for corruption.

Arrested and held over the weekend, O’Sullivan was released on R20 000 bail after a brief court appearance on Monday. He faces a charge of violating Section 26 B of the Citizenship Act because he had South African, British and Irish passports with him and had used his Irish passport to enter South Africa months earlier.

Surprisingly, O’Sullivan declined to comment, saying his lawyers had agreed with the prosecution that he should not speak to the media. But there is talk that he is now also being investigated for treason.

Increased disregard for accountability

Author and columnist Max du Preez, who spent many of his early years exposing apartheid-era dirty tricks, penned a column earlier this week in which he warned that South Africa is in imminent danger of slipping into the kind of police state that Russia has become under Vladimir Putin.

In addition to the recent incidents involving O’Sullivan, Nyanda and Malema, Du Preez wrote that there is a long list of other “burglaries, intimidation, trumped-up criminal charges, kidnappings, assaults and even assassinations … where the victims were critics of the police or ANC figures”.

On Wednesday, Du Preez said he didn’t believe these incidents were as random as they are being billed. “I covered much of the final years of PW Botha’s regime and I have a radar for these things. I believe they are just the tip of the iceberg.”

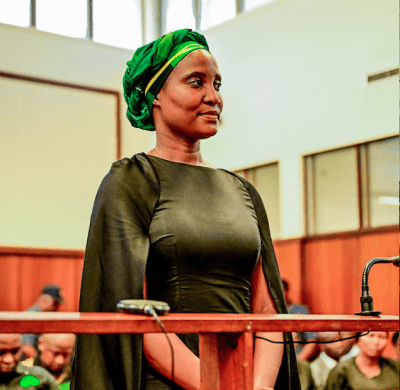

The intimidation of critics can come in various forms. Another widely seen example is the manner in which the public protector, Thuli Madonsela, was vilified over her pursuit of Zuma’s Nkandla case and the Hawks threatening to arrest Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan unless he answered their 27 questions about a South African Revenue Service investigative unit.

- Read: Madonsela wants Hawks investigation of her conduct dropped

- Gordhan releases statement on Hawks questions

Johan Burger, of the Institute for Security Studies, said existing information showed an increased disregard for accountability on the part of some government ministers and institutions, and the manipulation of key appointments in the criminal justice cluster.

For now, labels such as the “Prince of Nkandla” and “Commander-in-Thief” are coming hard and fast as President Jacob Zuma’s conduct over Nkandla escalates into an unprecedented call for united public defiance to ensure his removal from office.

This comes on the back of national outrage over claims that the Gupta family have captured key state-owned companies, thanks to their association with the Zuma family.

Although Zuma and the Gupta family have become the poster boys for state capture, the reality is that the rot runs so deep that it stretches from the highest echelons of government right down to the paperclip orders.

The non-governmental organisation Accountability Now’s Paul Hoffman said: “Ever since Jacob Zuma’s victory at Polokwane, the direction of politics in South Africa has been moving towards the creation of a patronage system to protect him and those close to him.”

Corruption Watch figures for 2015 found that 66% of cases reported stem from national, provincial and municipal levels. It listed abuse of power as one of the most common forms of corruption at 38% of cases.

A senior government insider said this week: “The thing is, state capture cannot happen without protection. And, for that, you need the right man or woman in a job somewhere where it matters, someone who would look the other way.”

Some recent casualties, whose ousting has led to a flood of civil court actions, include the former Hawks boss, Anwa Dramat; the Independent Police Investigative Directorate head, Robert McBride; the former Gauteng Hawks boss, General Shadrack Sibiya; and the former Asset Forfeiture head, Willie Hofmeyr.

Civil society organisations such as Freedom Under Law, the Council for the Advancement of the South African Constitution (Casac) and the Helen Suzman Foundation have made sure that several questionable government appointments in the criminal justice cluster were tackled in court.

But, although they have scored important victories, in some of these cases the government or the ministers responsible are yet to abide by the courts’ orders.

Lawson Naidoo, the executive secretary of Casac, said the integrity of institutions of government was important to ensure that democracy was not compromised. But the appointment of some men and women appears to be part of an orchestrated attempt to capture the criminal justice system. He added: “There is a perception out there that institutions of state are being used against elements of civil society who have been critical of government. And, that is worrying.”