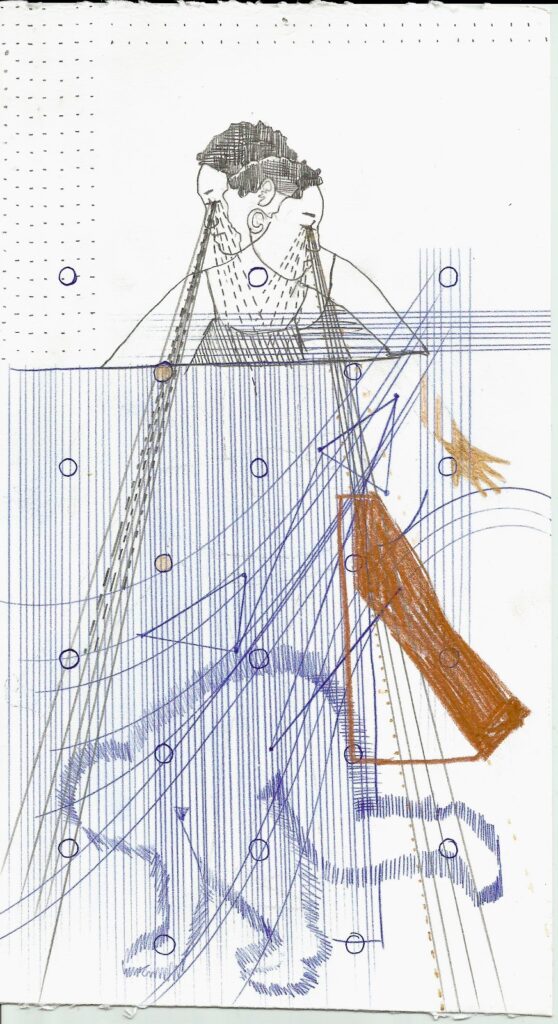

Study (Sepia Scallop), one of the works from Pamela Phatsimo Suntrum’s collaborative book ‘There are Mechanisms in Place’

From customs of storytelling within the slave quarters of enslaved Blacks to the prolific literary output of writers during the 1970s and 1980s, Black women have long been deploying narratives to embody their values because the narratives give voice to their shared experiences of, not only “hard physical labour”, but social and emotional labour as well … Thus, Black women’s fiction represents a canon of moral and spiritual thought and thereby constitutes sacred texts.” — Briona Butler, Pursuing The Canon: Black Women’s Fiction As Sacred Texts.

There are Mechanisms in Place is a complex constellation of text, poetry and visual analysis as a response to Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum’s practice, or more precisely her exhibition bearing the same name, which was staged at the Michaelis Galleries in Cape Town during 2018.

Frustrating the hard and imposed lines of fiction vs nonfiction, the publication does not simply explain the exhibition, but rather offers alternate engagements through dialogue, interruption, assembling and gathering. Each of the contributions could stand on their own, however, they remain relational and connected where the different formats offer an interesting interaction between the visual, the textual and the intertextual.

The book is edited by two Black women, Nkule Mabaso and Nomusa Makhubu, who have continued to offer their intellectual labour with the art landscape over many years, doing so rigorously and generously. The more time I spend with the book, the more Briona Butler’s words ring true. Butler presents a case for Black women’s creative output as sacred texts — more specifically writing in relation to Gwendolyn Brooks’s 1953 novel Maud Martha. Just as Maud Martha is Butler’s sacred text, There are Mechanisms in Place is a sacred text to me.

Butler claims the following:

- Sacred texts can make meaning of ambiguity;

- Sacred texts offer discursive tools with which Black people can excavate the meaning potential of their inherited legacies of struggle and resilience;

- Sacred texts provide language systems; and

- Sacred texts shape visions of liberation, even as the reader struggles to define what it means to live justly, as well as empathically.

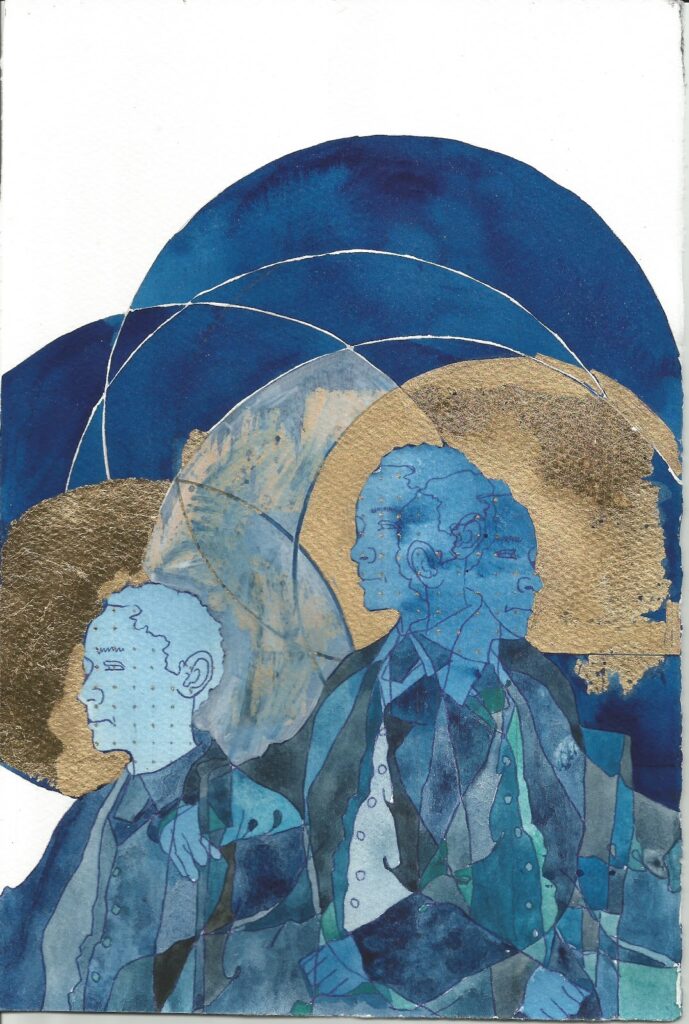

Study (Three Blue Suits)

Study (Three Blue Suits)

Through the creative efforts (intellectual and physical labour) of Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum, Nomusa Makhubu, Nkule Mabaso, Makhosazana Xaba, Thuli Gamedze, Amie Soudien, Toni Stuart, Bonolo Kavula, Philiswa Lila, Refilwe Nkomo, Amogelang Maledu and Simnikiwe Buhlungu, this book functions as a sacred text — it offers a new language through which to consider and excavate the meaning potential of our legacies of struggle and resilience, particularly in relation to decoloniality, following from the events of the student protests in 2015.

The 2015 student protests, of course, were when Minister of Higher Education and Training Blade Nzimande uttered the words: “It is a challenge, but I wouldn’t call it a crisis. A crisis implies that the situation is so bad that there are no mechanisms to deal with it. There are mechanisms in place.”

Both Sunstrum’s exhibition and the title of this book critically engage Nzimande’s threat to the students. Interestingly, perhaps one should say tragically, this phrase — “There are mechanisms in place” — serves as a warning to student protesters, while also serving as assurance to those who are interested in upholding the status quo …. a perverse Scout’s honour to the capitalist class who own most of society’s wealth and means of production.

“I am interested in how this ominously delivered threat served to confirm that the historical mechanisms that were once in place to ‘deal with’ student uprising are indeed still ‘in place’ now.” — Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum

Mechanism (noun):

- a system of parts working together in a machine; a piece of machinery; similar: apparatus, tool, device, implement; or

- natural or established process by which something takes place or is brought about; similar: procedure, process, system, operation, method.

Both definitions presented suggest the workings of something innate and unquestioned. Although Nzimande is not explicit in detailing the mechanisms he is alluding to, we know that systems of oppression are, in fact, pervasive, omnipresent and remain “at work”. To put it crudely, the devil works hard but racism, patriarchy and capitalism work harder!

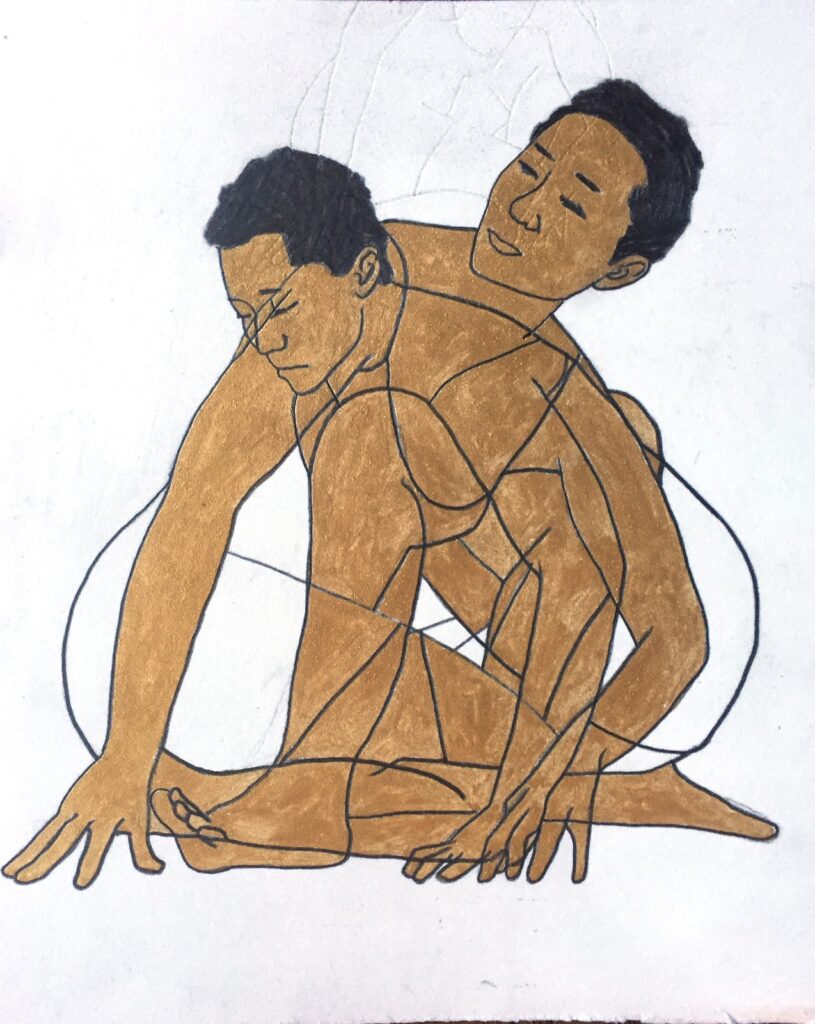

Study (Figure #3)

Study (Figure #3)

Sunstrum’s practice encompasses drawing, painting, installation and animation. Her work alludes to mythology, geology and theories on the nature of the universe. We are not only confronted with the amalgamation of fantasy and the subterranean, but also with the difficult questions that both ancient ancestors and futuristic scientists have been mulling over centuries: Who are we? Why are we here? How was the universe made? What is it made of? And, of course, these questions, as well as the specific ways of knowing, are influenced by power.

In her 2018 exhibition, There are Mechanisms in Place, Sunstrum presented a 10-channel animation installation: Homing Device. The installation, which includes audio by Kwelagobe Sekele, displays animation created with collages from 19th-century photography pioneer Eadweard Muybridge’s animal-motion studies.

The work introduces avian flight, particularly the navigational abilities of homing pigeons, as a setting off point from which to think through place and home. To Gamedze, this is an invitation to reflect on home, in motion. To Nkomo, this is a reminder of the time we could fly; “Ruptures of red and orange. Crying crayons across the sky”. To Stuart, the gimbal of homing is “a weighted shadow falling through the skies”.

To Mabaso, Homing Device seems to be a gravitational pull towards a region of space-time where nothing can escape, resulting in a multilayered, multifaceted tessellation of an art historical and ornithological ensemble through the internet — crows, American flamingos, falcons, roosters, Paul Klee, Gladys Mgudlandlu, Vincent van Gogh, Helen Sebidi, Jane Alexander, Leonora Carrington, Peju Alatise and many, many more.

Spanning 18 pages, Mabaso’s response, titled, “This Visual Something Something”, is a story about birds that is not about birds. Kavula’s response to Sunstrum’s practice is in the form of an illustration that seeks to draw out the manner in which her practice aids in the process of thinking about the “otherworldly”. Kavula homes in on the image of the maternal figure, which recurs in the work. She notes: “The figures have a presence, but they are never familiar enough to have an identity.” Sunstrum’s work becomes a discursive tool for Kavula and, in turn, Kavula’s response becomes a discursive tool to us — a sacred text born of another sacred text.

What is most interesting to me about the project is its collaborative spirit. Of course, Mabaso and Makhubu have long offered us models of partnering and partnership. In 2019, the pair worked together to curate the South African pavilion for the 58th Venice Biennale with the theme “The stronger we become”, which sought to highlight the resilient spirit of South Africa and its citizens.

Study (dikeledi)

Study (dikeledi)

The current context of the pandemic has brought to fore, in more explicit ways, the realities of isolation and loneliness. We’re reminded of the many people across the world who experience isolation to varying degrees. With this context in mind, the value of alliances, joint effort and partnerships is undeniable. It is my belief that collaboration, the kind where all parties are empowered to bring their full selves, is, in fact, a powerful philosophy that pushes against the individualist and hierarchical social context we find ourselves in. It is the antidote to hegemony and, therefore, contributes to decolonial work.

There Are Mechanisms in Place (Michaelis Galleries, UCT) is a collaborative book on Sunstrum’s work, based on the artist’s solo exhibition of the same name presented at Michaelis Galleries from August 23 to September 21, 2018. It is edited by Nkule Mabaso and Nomusa Makhubu