Uhuru Phalafala, Radna Fabias, Ishion Hutchinson and Toni Stuart in an Open Book Fesival panel in 2019. This year, the festival has moved online. (Photo: Retha Ferguson)

Many arts festivals have had to rethink their strategies for this year because of the various lockdown levels, which the country is still reeling from.

One such event is the Open Book Festival, which takes place annually in Cape Town. For this year’s installation the organisers have teamed up with Cape Town-based bookstore The Book Lounge to present the Open Book Podcast Series, which started last week and will run until 12 November.

The first episode features Bongani Kona in conversation with Nigerian author Helon Habila about his new novel, Travellers. Habila is professor of creative writing at the George Mason University in the United States. He has previously won the Caine Prize and the Windham-Campbell Prize for Fiction.

The cover photo of the book is by Ian Berry, a British photojournalist who was based in South Africa in the early 1960s. He is credited with capturing the images of scattering masses being shot at the backside by the South African police during the Sharpeville massacre. Later, in court, these images would prove invaluable to underpin the innocence of the peaceful protesters.

The image on the cover of the novel captures an African couple in what seems to be a relaxed mood in a café in Fordsburg, Johannesburg. The café serves both black and white patrons. The only thing is, this is South Africa circa 1961 and the Group Areas Act is in full force. The possibility of a police unit pouncing and arresting everyone on site is not far-fetched.

The cover to Helon Habila’s new book Travellers, which forms part of the festival’s podcast series. (Supplied)

The cover to Helon Habila’s new book Travellers, which forms part of the festival’s podcast series. (Supplied)

This is the tapestry that Habila works on thematically in his new work, Travellers. Interestingly this is the working title of a series of paintings that one of the characters, Gina (the narrator’s wife), is busy with during Book 1, “One Year in Berlin”. (The book is divided into six “Books”.)

Gina is a fine artist who has just been awarded a fellowship to work on her paintings. For her theme, she needs real refugees, or travellers, to sit down for her to paint. One of them is Mark Chinomba, who is running away from an oppressive patriarch back in Malawi. He has joined his uncle in South Africa, who understands his precarious situation.

Mark is a young student who wants to be a filmmaker — and whose birth name was “Mary”. This then is the “real” story behind his sour relationship with his preacher father back home. His father keeps on saying that his child wants to embarrass the family and the congregation with his career choices. But at the heart of his displeasure is Mark’s gender orientation. Unfortunately, exile does not afford him a haven either. So, Mark must keep on travelling.

Book 2, titled “Checkpoint Charlie”, delves into the story of Libyan refugee Manu and his attempts to survive in a foreign land. The doctor-turned-bouncer works in a discreet nightclub serving upper-class white women. He ends up in a relationship with one of his clients, who insists that she wants to see his young daughter. She has horses. Perhaps the daughter would be interested in riding them, she suggests.

But as the lovers’ relationship develops, the client’s husband resurfaces, giving the story a biting edge at its ending. Although the conclusion was open-ended, this might just be the beauty of the story for some readers, after all.

Other parts of the novel, or “books”, follow suit with their stories. They are self-contained, with the overall title, Travellers, linking them.

Habila himself is a “traveller”, having left Nigeria after winning the Caine Prize, but always coming back: “So, the movement … I have been an outsider, you know. I have been a stranger and I’ve always had to kinda reimagine home and reinvent myself in these new places and acclimatise,” he notes on the podcast.

Migration and its perils are recurring themes in the book. As Habila says in the interview with Kona, it is a current and future issue the world must contend with. Since the aftermath of World War II, migration has been a permanent feature around the globe. So, what needs to be done? “The best thing the world can do … we have to reimagine our national borders. We have to reimagine the idea of travel itself,” he says.

Asked how the coronavirus pandemic has personally affected him, Habila paints a picture of the kind of uncertainty writers face: “You write the book by yourself and now you’re discussin’ the book still in the same room that you wrote the book in. So, it’s a kind of crazy feelin’…”

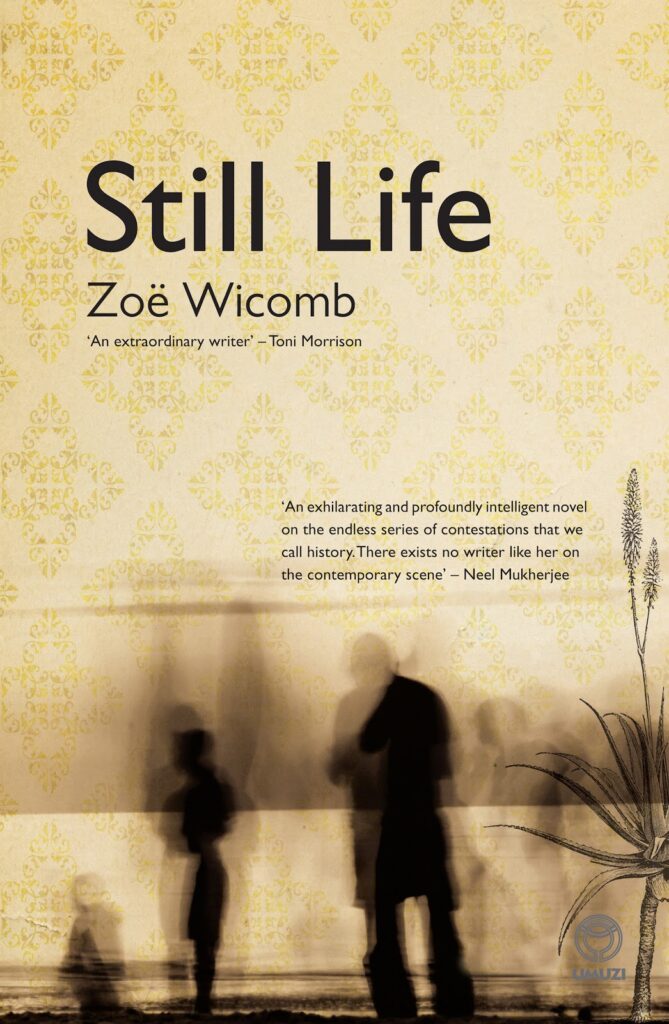

Zoë Wicomb’s Still Life is the subject of one of the Open Book Festival’s podcast series

Zoë Wicomb’s Still Life is the subject of one of the Open Book Festival’s podcast series

The second episode of the podcasts features Zoë Wicomb, who is described on the cover of her latest book, Still Life, as “an extraordinary writer” by Toni Morrison. She is the author of You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town, David’s Story, Playing in the Light, The One that Got Away and October, among other works.

Other panellists on the episode, which is described by the organisers as “a discussion about engaging with historical narratives from new perspectives and striking a balance between fidelity and irreverence in retelling stories”, include Zimbabwean writer and lawyer Petina Gappah and writer, activist and academic Helen Moffett. The latter’s debut novel, Charlotte, came out this year. The panel is chaired by Efemia Chela. She was shortlisted for the Caine Prize in 2014 and is a contributing editor to the Johannesburg Review of Books.

Locals on this year’s podcast edition of the festival include memoirist Sara-Jayne King, internationally acclaimed writer Lauren Beukes and multi-skilled artist Phumlani Pikoli.

To access the podcasts, listeners can use any of the standard podcast apps, or find them on the Open Book or Book Lounge websites. The podcasts are available to download and listen to at your leisure.