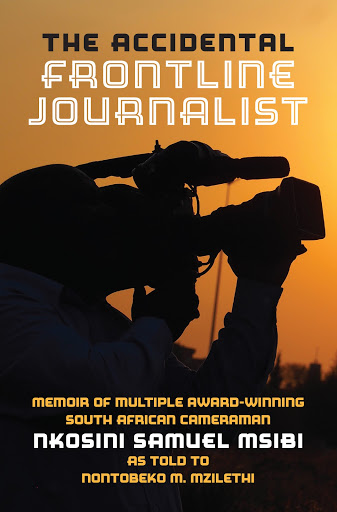

Veteran cameraperson Sam Msibi’s memoir, The Accidental Frontline Journalist, reveals what happens after the credits have rolled, including the trauma that arises from documenting brutality. (Photo: Siphiwe Linda)

Sam Msibi loves to narrate how he got the moniker “Scud missile”. It was in 1991, during the Gulf War. He was working with the Britain-based Worldwide Television News (WTN) in Israel when Iraq launched a missile strike on Tel Aviv. Instead of heading for the bunkers with the rest of the hotel guests, Msibi’s instinct kicked into gear and he ran to his hotel balcony, his camera loaded and ready to fire. Except he was buck naked. His colleagues at WTN also nicknamed him “Sam-Cam” in recognition of the exclusive footage of the Scud missiles he had shot.

In the adrenaline-intensive world of TV news, the cameraperson is of paramount importance. Instinct instructs the rest of us to flee from danger; the lensman hurtles towards it, with the speed and stealth of a guided missile, propelled by a seventh sense that contradicts every normal instinct and semblance of sanity.

It’s a perilous dance, knowing how, when and when not to shoot, while never averting one’s eyes. And, all too often, the seemingly invincible frontline shooter becomes invisible when the camera is switched off. But in The Accidental Frontline Journalist, veteran lensman Sam Nkosini Msibi has chosen to reveal what happens behind the lens after the credits have rolled.

It is a vividly hewn memoir that straddles three decades of the most seminal events in South African history — not to mention the rest of the continent and hotspots around the world. For Msibi, the political and personal are on a constant collision course and entangled in every history is an extraordinarily intimate trajectory. Msibi’s story speaks to the African Everyman who has transitioned from BC (Before Change) to AD (After Democracy), and rips the band-aid from the skin to expose not-quite-healed scars, both psychological and physical.

Like an oral historian, the 59-year old Msibi has narrated his story to communications specialist Nontobeko Mzilethi. She has provided a meticulous timeline of Msibi’s life as son of the soil; his father, Zephania, was a migrant labour and his mother, Ellie, a farm-hand.

We read Msibi’s evolution from an impoverished child in Mbizaneni, in KwaZulu-Natal, to the clever-but-still-poor school kid in the township of oSizweni; earning pocket money as a garden “boy” in the plush, white suburbs of Newcastle; becoming a wedding photographer, teacher, sangoma, multi-award-winning, internationally acclaimed cameraman; and so much more.

Although she doesn’t always succeed in evoking the raw viscerae of Msibi’s journey, Mzilethi has delicately intertwined his personal milestones and hardships with South Africa’s most defining political watersheds.

Sam Msibi taking footage of his colleagues during the protests against SABC retrenchments. (Image courtesy of Hazel Friedman)

Sam Msibi taking footage of his colleagues during the protests against SABC retrenchments. (Image courtesy of Hazel Friedman)

One of the recurring refrains of Msibi’s narrative is the unmitigated trauma of documenting brutality — a trauma that haunts every frontline journalist, despite the most ardent efforts to soften the jagged edges through alcohol and other elixirs.

As Msibi relates, not even the stiffest of whiskeys could erase the memory of burnt, mutilated corpses lying rag-tag in the pre-democracy killing fields of South Africa, piled high in the churches and schoolrooms during the 1994, or decomposing in makeshift mass graves during a stint in Mogadishu, Somalia. Death disfigures even the most hard-living, die-hard of lensmen.

As Msibi relates, not even the stiffest of whiskies could erase the memory of burnt, mutilated corpses lying rag-tag in the pre-democracy killing fields of South Africa, piled high in the churches and schoolrooms during the 1994 Rwanda genocide, or decomposing in makeshift mass graves during a stint in Mogadishu, Somalia. Death disfigures even the most hard-living, die-hard of lensmen.

As Msibi recounts: “We frontline journalists only had our cameras. We did not carry bombs. We had nothing to protect ourselves from potential harm.”

Long before “mindfulness” and “post-traumatic stress” became trendy buzzwords, there was no such thing as a debriefing, counselling or any of those panaceas required by even the most battle-hardened among us. Consequently, the harm has become permanently seared into Msibi’s psyche; yet, his calling is to return compulsively to the trenches, to the scenes of the crimes, until his soul can take no more.

Msibi was among the first black news cameramen employed by the SABC, and his memoir also provides an insight into the systemic racism that remained endemic in the SABC even with the advent of democracy. He joined the broadcaster in 1983, when separate entrances, toilets and cafeterias were still mandatory. Although he subsequently left to join several other broadcasters worldwide, he ultimately returned to his alma mater, where he currently works.

From the mid-1980s to mid-1990s, black journalists were the unsung heroes of the industry; covering stories of unrest in the townships where they lived, exposed to reprisals from which their white colleagues were largely immune.

A case in point was the United Democratic Front (UDF) meeting in KwaThema in 1984 . As an employee of the reviled SABC, Msibi was forced to do the walk of shame out of the meeting, heckled by an irate crowd who regarded him, at best, as a sell-out to be shunned; at worst, as a traitor deserving to be necklaced. In April 1993 he was shot and seriously injured. He attributes his survival to spiritual anointment — a supernatural sheath that, since his childhood, has shielded him from death and soothed his wounded psyche.

Sam Msibi’s memoir is part tribute to his colleagues, part cornucopia of perilous assignments. (Published by Porcupine Press)

Sam Msibi’s memoir is part tribute to his colleagues, part cornucopia of perilous assignments. (Published by Porcupine Press)

Of course, white journalists working during that time and after, have also displayed inordinate courage and sometimes paid the ultimate price. But black journalists continued to be prejudiced in terms of -salary and acknowledgement. Their pioneering contribution remains a neglected history.

As Msibi insists: “Their names need to be honoured so that the next generation can know them and appreciate what really happened for this country to be liberated.”

The book is partly a tribute to his colleagues, partly a cornucopia of perilous assignments. But Msibi is also a man of extraordinary generosity, gentility, humour and humility. For example, he harboured an unrequited infatuation for none other than the late Zindzi Mandela — a crush he was too shy to disclose even to his friend, her father former president Nelson Mandela, when he was chosen to accompany the statesman to document his life story.

He recounts his accomplishments and adventures with unabashed glee, sometimes anguish, but never arrogance. And as one of many journalists who have travelled with Msibi through trepidatious terrain, I too have some anecdotes: like the time our vehicle broke down in Cabo Delgado. Inside were intrepid investigative journalist Estacio Valoi, a bunch of poachers, myself and Msibi, and an animal horn of dubious origin, while a couple of Mozambican cops towed our car to the closest petrol station, oblivious of our illicit cargo. Or when we had to make an early-morning escape from a murderous cartel of illegal miners in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with Msibi displaying the driving skills of a stuntman.

He was, is and will always be the kind of cameraman you want in your corner.

There is a particular poignancy to this memoir in the context of Covid-199 and an SABC currently on its knees, crippled by years of mismanagement. The best, brightest and most experienced will have to compete for their jobs with a new generation of lensmen for a fraction of their current salary.

Accidental or not, there will never be another Msibi. But he is sanguine about his future; he’s briefly returned to his KwaZulu-Natal roots to spend Christmas with his beloved mother, Ellie, who is a sprightly 92-year-old.

Sam-Cam, the Scud missile, is again a son of the soil.

The Accidental Frontline Journalist (Porcupine Press) will be available in book stores in January.