A scene from Jefferson Tshabalala's J. Bobs Live — Seen Pha kwa J.B! (Photo: Rudy Motseatsea)

The 45th edition of the National Arts Festival was always going to be fraught with difficulties once the Covid-19 pandemic made clear that South Africans would not be able to gather in the Eastern Cape town of Makhanda for its annual showcase of music, theatre, art, dance, comedy, literature and panel discussions — a reflection of what the country is thinking and feeling.

For the organisers of the festival this meant, after President Cyril Ramaphosa’s announcement of a lockdown in March, reworking a programme that had been almost finalised much earlier. It demanded imagination and nimbleness in curating a shift from mainly live performances to work that could be adjusted, filmed and then presented on the internet. Or, new work that used the online medium and the possibilities it offered in concept and practice, to create something fresh.

The former was most evident in pieces such as Standard Bank Young Artist for Theatre Jefferson Tshabalala’s edgy J.Bobs Live — Seen Pha kwa J.B! which used rap, beat-boxing and acting to take the audience through a series of hilarious episodes that scratch at the scabs of race relations in society and consumerist cultural production. Performed (and filmed) in a studio that is both stage and set, it blurred the lines between theatre, television and reality with insouciance.

Online-specific work included Leila Anderson and Stan Wannet’s Screen Saver, which used the medium of the computer to create an artwork that required a patience increasingly anathema to the hi-tech, instant-gratification norms of our age. Touch your mouse, and the artwork is disrupted; leave it alone, and it reveals itself over 10 minutes.

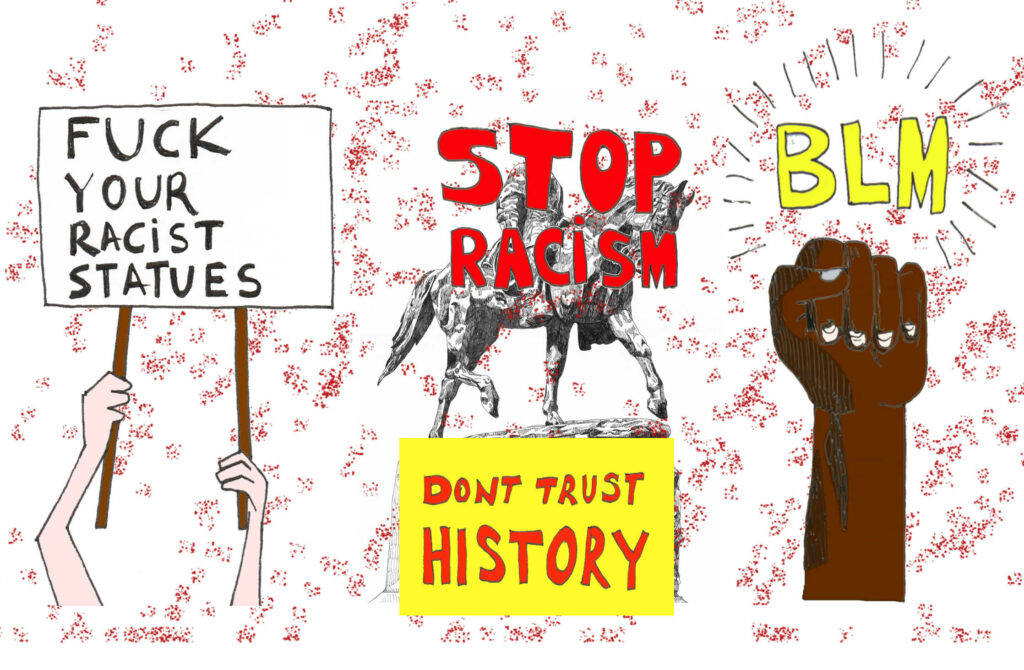

Marcio Carvalho’s Who do we Come to H(a)unt, meanwhile, allowed people to wreck-claim statues, ranging from Belgium’s King Leopold II to the horrendous Nelson Mandela bronze in Sandton, Johannesburg. It tapped into current conversations in the Black Lives Matter movement and others about what to do with the bronzed memorialisation of racism and slavery that become everyday sites of trauma in the public’s eye-line.

Madosini, a master of instruments and composition, was the featured artist at this year’s National Arts Festival. (Simphiwe Nkwali/Sunday Times)

Madosini, a master of instruments and composition, was the featured artist at this year’s National Arts Festival. (Simphiwe Nkwali/Sunday Times)

For the punters, this shift to a virtual festival meant logging in to, rather than trekking out to, the stages, galleries, markets, street stalls, pop-ups, bars and restaurants that make the festival.

It is a shift that sometimes deepened a sense of lockdown alienation, of being alone, because it highlighted so starkly what had been lost: the joyous magic of the live experience and its ability to invoke immersion, meditation, rumination; the individual act of attendance converted into a communion; the shared experiences and spontaneous responses within that concord, which lingers long after the performance ends; the provocations inherent in the engaged work that cause passionate, boozy debate at the Long Table until just before sunrise — and, just maybe, some solidarity and action.

Those had all disappeared. To be replaced by a buffering sign, the WhatsApping, a household in the background — all intrusions into interaction. Where previously one’s eyes and attention had the freedoms of engagement, that experience was now mediated by cinematographers, directors and editors. One’s reflection on work became more solitary and lonely.

This is, obviously, not the festival’s fault — merely the signature to our times. If anything, such adversities appear to have strengthened the National Arts Festival: from creating the online marketing legacy of a virtual Village Green to a virtual Fringe Festival. Nor did the curatorial difficulties undermine the standard of work. Adaptation to a “new normal” made for provocative, challenging work that, in several cases, amplified this moment’s requirement to listen to voices that have been historically marginalised, ignored or subjugated.

This was especially so for black female artists on the curated programme. The festival’s artistic director, Rucera Seethal, emphasised the importance of facilitating and ensuring their presence at the festival because many, especially single mothers, had the additional, solo task, of home-schooling children over the production period, which coincided with a hard lockdown — a consequence of structural sexism and dilettante baby-daddies.

A stellar programme included Standard Bank Young Artist for Dance, Lulu Prudence Mlangeni, who returned to her Soweto hood for a documentary, Lesedi: The Rise of Lulu Mlangeni. The film brought together autobiography and dance, her life and her life’s work, to explore the anti-black, anti-female milieu she had to fight against and rise above. The personal-political nature of the film meant it fitted into an oeuvre that includes Question Mark and Confined, earlier pieces that examined the life of Winnie Madikizela-Mandela — a figure too often cast in black and white, rather than the shades of nuance she deserved.

For those hankering after “Grahamstown”, Qondiswa James’s semi-autobiographical theatre piece, A Howl in Makhanda, explored the hypocrisy inherent in the exclusionary identity of a “frontier town” characterised by posh private schools, the University Currently Known as Rhodes, 1820 colonial settlers and their farmer descendants. Set in Makhanda’s elite Diocesan School for Girls, it follows four teenagers — two black and two white — through a schooling system that one aptly describes as “part of a plan to make [us into] a dutiful machine for capitalism, hardwired for conformity”.

The daily routines of boarding school life, attending classes, shit-talking and smoking cigarettes are punctured by conversations about the culture of body shaping and shaming in these institutions where racism is rife, of the sexualisation of young girls in broader society and themes of depression, bulimia, white privilege and rape culture.

Marcio Carvalho’s Who do we Come to Ha(u)nt, which allows people to wreck-claim statues.

Marcio Carvalho’s Who do we Come to Ha(u)nt, which allows people to wreck-claim statues.

The different outcomes reserved for two of the main characters — one black, the other white — when both are found guilty of the same transgression, exposes the racist hypocrisies at the school, but also in a South Africa where the rainbow nationalist project is failing because it asks so much of black people, and so little of whites. A razor-sharp script that references Sylvia Plath and Kurt Cobain, combines with fine acting, directing, and filming of the performance to ensure a powerful piece of theatre.

Dumile Feni: 4 Provocations gathered four of the continent’s premier dancers and choreographers; Zimbabwean-born, New York-based Nora Chipaumire; 2018 Standard Bank Young Artist for Performance Art, Chuma Sopotela; British-Rwandan Dorothée Munyaneza and Ivorian Nadia Beugré to consider the work, and life in exile, of the artist Dumile Feni. The artists delivered work of staggering power and feminist revisionism, which will be developed individually for the festival and the Institute for Creative Arts.

In (another) township manifesto, Chipaumire considers the lionisation of male freedom fighters while their female counterparts, or the women they leave behind to deal with the politics of the everyday, are cast into the shadows. She also examined the lonely pain of exile, all set to a blistering soundtrack, which included Zimbabwean artists Thomas Mapfumo and The Blacks Unlimited, and Dorothy Masuka, as well as Nigerian Sonny Okosun’s Fire in Soweto.

Sopotela’s work, A short tribute to Zwelidumile Geelboi Mgxaji Mhlaba “Dumile” Feni was performed and filmed within the claustrophobia of a square no larger than a small, four-walled shack. Instead of corrugated metal and cast-away wood, the walls were made of blankets — the blanket of the matriarchy, poverty, defence, rural nostalgia, warmth and protection. Sopotela’s room was furnished with nothing more than a shovel, potjie pot, elemental heater and storage chest. All these props were evocatively used as parts of the performance and the filming process.

“I woke up to a thought that I should build a grave,” are words that hang over the piece as Sopotela awakened with blackened, puffy eyes that bore a deep violence stretching back centuries. Her performance raised questions about creating art in poverty, but also examined con- temporary themes such as the anxi- ety around death and burial during a pandemic.

The featured artist at this year’s festival was Madosini, the septuagenarian guardian of traditional Xhosa music from Pondoland in the Eastern Cape. A maestra of umrhube (mouth bow), uhadi (music bow) and isitolotolo (Jew’s Harp), Madosini is a world music icon whose work speaks to both the spiritual and the everyday material aspects of the human condition.

Mini-documentaries were released daily during the festival’s 11 programmed days. Each episode centred on one of Madosini’s songs as it traversed her life from a teenager playing the umrhube in the reeds of Pondoland as part of the initiation ritual for young girls to international acclaim. Archival footage, including from Poetry Africa in Durban and Womad in Reading, imbued the short films with a gorgeous sense of performance and personal insight.

One of the most powerful moments is when Madosini develops a personal and musical connection with Zanzibari taraab and unyago icon, Bi Kidude, at the Dow Counties Music Academy in 2004. Kidude died in 2013 at an age of about 103, but the interaction crystallises what towering continental giants these two musicians — whose musical genealogies trace back to spaces of mating and initiation, slavery, dispossession and oppression — are, as they bond over music and mischief.

It emphasised that despite man’s most violent attempts to subjugate female voices — to force them to “eat fear” and thus attempt to “turn the food in their mouth to sand”, as Jesmyn Ward describes in the novel, Sing, Unburied, Sing — these most eloquent guardians of our past and present remain essential to our collective futures.

All content, from the fringe and main festival, can now be streamed until July 31. nationalartsfestival.co.za.

This article was first published on New Frame