Queer activist and filmmaker Bev Ditsie provides compelling reflections in the film (Supplied)

“We’ve got hope, we’ve got a vision of a South Africa that is going to be different from what it has been. We’re over the moon, all of us, we’re on cloud nine and our people say hey, we have crossed the Red Sea and we are on our way to the promised land. All of us. Black and white together … God bless you.” — Archbishop Desmond Tutu, speaking at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), as shown in the film A New Country.

A New Country, like director Sifiso Khanyile’s older film, Uprize!, is rich with footage. It starts off with a Johnny Miller-style drone shot of a road dividing the neighbourhoods of the haves and have-nots — which could be anywhere in South Africa. It is a poetic, deliberately moving scene overlaid with television commentary from February 1990, tracking Nelson Mandela’s step by step walk “further into freedom”. Moving apace with the lumbering gait of the first democratically elected president, the clip tells us that the walk to freedom is, if you look around you, indefinite.

The archival footage — from Cyril Ramaphosa’s fateful march on Bisho in 1992 to Cecil John Rhodes’s statue being bundled off in black bags from the University of Cape Town lawns in 2015 — makes for an opening montage that is an appropriate compression of the real-time headiness of the past 30 years. But, as the dust settles and the talking heads emerge, what becomes clearer is that the past three decades have provided only the (regretful) clarity of hindsight and none of the coherence of supposed nationhood.

The markings on the ground now remain as they were then: not footpaths to reconciliation, but mere dividers of a maze. Through the interweaving of footage with the talking heads, as the audience, we also emotionally flit between these two states: the delirium of the lead-up to Mandela’s presidency and the blanks we have since drawn at every turn. Although the talking heads bring an air of measured austerity to the proceedings, tempering the ecstasy of the streets, they, too, are burdened at points by naivety, which they unpack as the story’s timeline moves along. Periodically, this turns into protracted noodling, because their class proximity means that they echo each other.

That is not to say splitting hairs about the past is a useless exercise — far from it; one must constantly reflect — but just as Tembeka Ngcukaitobi criticises the TRC for parading only the foot soldiers, the ruminations in this film emerge from only one strata of society, inevitably informing its tenor.

Luyanda Hlatshwayo represents the voice of the working class in A New Country (Supplied)

Luyanda Hlatshwayo represents the voice of the working class in A New Country (Supplied)

When Athol Williams speaks of the patchwork anthem being an example of compromise, he doesn’t take the analysis further by examining who and what the possessive determiners and pronouns in Die Stem referred to. So, although it can be argued that these times call for stridency, the sensibility at play here serves up a lot of restraint and, in some cases, respectability.

In a sense, this is not the fault of the filmmaking, but a function of South African society — the inability to take important conversations to their logical conclusion because of how inextricably bound up we are by the reality of being a settler colony. And so the euphemisms tumble out. “The private sector is not held to account,” says Kevin Bloom in one instance

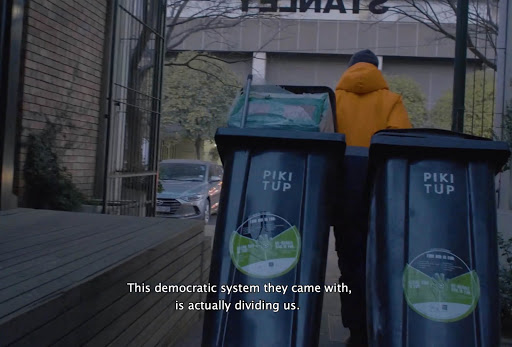

So although someone like Luyanda Hlatshwayo, a recycler, adds a somewhat divergent perspective, coloured, perhaps by a different sense of marginality than the rest of the commentators, his presence can be read as a form of tokenism.

A New Country, in and of itself, is not a politically naive film. There’s an acknowledgment that our systemic problems stretch back to the 1600s. Artist Masello Motana, in particular, sits against a backdrop inscribed with a litany of dispossession laws that precede apartheid and wretch the narrative of dominion from the sole preserve of the Afrikaners. “You dispossess by fire and blood and then you bring in laws to maintain order over what you have stolen,” she says.

There’s a realisation, to borrow from Maleven (the famed thug in Louis Theroux’s Law and Disorder Johannesburg), that the state has been “making example” of its citizens — the nuts and bolts of imperialism — with a recent timeline of repression stretching from Andries Tatane, through Marikana, right up to Fees Must Fall.

There is a crisp, systematic analysis, particularly from Ngcukaitobi, about the totality of the dispossession (land, cattle, minerals) and statistics and maps showing the almost unchanged pattern of that dispossession. But then, via the narration, there is a telling contradiction in the flawed semantic choice of referring to Marikana as a “tragedy”, as if not to ruffle the feathers of the very same power structure that is being critiqued.

Zara Julius argues that South Africans need more time to figure out a new path for the country, but only after confronting a collective post-traumatic stress disorder (Supplied)

Zara Julius argues that South Africans need more time to figure out a new path for the country, but only after confronting a collective post-traumatic stress disorder (Supplied)

As Zara Julius states, we have no clue how complex our history is. It is so complex, in fact, that some of these conversations “seem messy and unproductive”. At that moment, she sounds as if she is both inside and outside the film, speaking back to its tentative prognostic impulse.

But perhaps, underneath it all, there is a deliberate modesty to A New Country that sets it apart from other films attempting to tell a similar story. Compared to Khanyile’s other film, Uprize!, there is less of a discord between the talking heads and the raw footage. There is a concerted effort to balance the film visually, with older archival footage almost seamlessly melding with current manifestations of inequality to convey a continuum.

There are attempts, visually and narratively, to ground the film as a safe reflective space, quite possibly due to the involvement of Lesedi Molefi, who has featured in some of Lebogang Rasethaba’s films in which this style is employed. With Rasethaba, maker of MTV Base’s The People Versus series showing up in the credits as a story consultant, one can see tempered manifestations of his frenetically paced style rubbing up against Khanyile’s almost instinctive quietude. The composite is exciting, in so far as it layers the storytelling.

Perhaps this modesty is a good thing for A New Country, for it does not attempt to tread the exact same discursive path, for example, as Jihan el-Tahri’s Behind the Rainbow (which focused quite sharply on the sunset clauses, incumbency and the fissures within Mbeki’s ANC). A New Country operates with awareness of its predecessors and contemporaries and, therefore, ups the ante in other aspects — such as editing, its soundtrack and the use of multiple storytelling devices — to such an extent that the “objective” narrator isn’t too much of a nuisance.

Although Shane Cooper’s project, Mabuta, is sparingly used, there is enough in the sonic cues to adequately suggest the somnambulism of the new country.

Perhaps A New Country ’s ultimate triumph is in its clear, unhindered search for a new visual voice — in some ways a generational imperative — in a playing field in which telling the South African story is sometimes a game of partisan politicking at the expense of nuance.

But you can still sense elements of the tip-toeing that is our national consciousness. At the end of the day, however, this is the vantage point of those who have, to an extent, tasted the bittersweet fruits of so-called freedom. Their disaffection is just as compelling as that of the masses, even as the end game is expressed with equivocation.

A New Country will be screened as part of the Encounters Documentary Film Festival, which runs from August 20 to 30 online. Visit the website to purchase tickets.