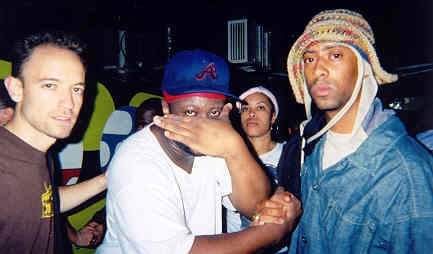

Stahhr collaborated with DOOM on three of his released albums after meeting him at a show in Atlanta at the turn of the century. (Photo: Roy Handy)

“I view death in a different way than a lot of people do, so I am happy for him, you know what I mean, because he got out,” says Atlanta-based emcee Stahhr as I offer my condolences to her, six days after the announcement of DOOM’s passing on 31 December 2020.

Stahhr collaborated with the masked artist most popularly known as MF DOOM on three of his released albums, Take Me To Your Leader (credited to King Geedorah, another one of his characters), Mm.. Food and Born Like This.

“My issue is more with the behaviour of other people after a death. I totally understand why they [his family] waited two months. I get it all. More people should do that so that their families can have time to breathe and get their affairs in order,” she says.

“He was literally able to rest peacefully because nobody knew he was even gone. I think it’s a wonderful idea.”

We are speaking via a WhatsApp call, discussing the effect that DOOM, who moved from New York to Atlanta as he was establishing the second phase of his career at the turn of the century, had on her own career.

How did you connect and how did that affect the trajectory you were already on as an emcee?

When I met DOOM, I had been rhyming for about eight or nine years. I started rhyming in high school. When I met him, I was already making noise on the Atlanta scene. I met him at a Micranots show, labelmates of ours on Subverse. This might have been about January 2000. I was performing with the Micranots and I freestyled.

He introduced himself to me afterwards and said, “Yo, you dope.” I said, “Thank you.” I let him know that I’d been listening to him since I was a kid, KMD, whatever, and we ran into each other again in 2001 after I had already put out my single with Subverse. It was a Subverse showcase on Halloween. We met backstage and he was like, “Yo, I wanna work with you.” We exchanged information and next week I was at the house and I was working on the verse that would end up being on Next Levels.

The work that I did with him put me on a way bigger stage and gave [me] a way bigger audience because he was such an established artist. It was a great thing for me at that point in my career. He took me under his wing; he had a lot of faith in me. He gave me a lot of jewels and guidance.

You are on three of his albums. Is there a lot of other material that you recorded together that could possibly still come out?

There are some things that haven’t come out, but it wasn’t like a whole lot. We never got to really get started with the Angelika project. That was gonna be my Metal Face release. It was something that we discussed, but we never revisited it.

Had you started writing for that?

No. It was something that had just been discussed. Here is the thing about DOOM, okay. You can be in touch with him and then not be in touch with him for like years, and then be back in touch with him. In that space of not being in touch, I was working on my own stuff.

DOOM pictured with Peanut Butter Wolf, Stahhr and Madlib. (Image courtesy of Stahhr)

DOOM pictured with Peanut Butter Wolf, Stahhr and Madlib. (Image courtesy of Stahhr)

What brought DOOM to Atlanta?

I really felt like it was something that was meant to happen. I didn’t ask a lot of questions around him. I was more in the moment, because you wanted to soak up whatever game you could soak up from him.

Let’s talk about the song Guinessez. That beat and subject matter are a perfect match, and your execution is flawless. Can you tell me about the foundation of that song?

He gave me that beat. He said, “I want you to do whatever you want to do on this beat. I want you to bring a feminine perspective to this album. You’re gonna be the balance.” After I wrote the song, he didn’t let me know that it was a food-theme thing, so I changed the name because it was initially called “Purple Heart Love”. I changed it to Guinessez so it could fit the food theme.

Do you remember writing those verses?

I wrote the song back in 2003. I was in a relationship at the time that wasn’t going the way I wanted it to go. A lot of that was written from a personal experience type of thing. When I wrote that song, I had no idea that it was gonna end up as a song by Angelika because that was actually a Stahhr song. Angelika was a personality that I never got to explore. Angelika actually wrote Still Dope.

What were some of the things you picked up from him?

He told me not to date my music. When you are writing [or rapping], don’t say the year. He [also] said when you are approaching something, you are a writer. You should be able to write about anything. That was why he had all the different personalities.

He said, “That is your creative licence, use it.” You don’t have to personalise everything and that will give you more freedom.

And that’s true because when I met him I was going through my own personal growth and spiritual awakening and I didn’t want to address certain subjects.

That’s kind of where the whole Angelika thing came from. She was going to be the alter ego [who] could talk about all of the things that Stahhr didn’t feel comfortable talking about.

That’s why I say Still Dope was an Angelika song because it was all aggressive: I was talking my shit and I didn’t necessarily come that hard, because I was dealing with different spiritual stuff.

I was part of different communities and I didn’t want to have music I couldn’t play around kids or whatever. I wasn’t separating my personal life from my art, which was something that I learnt from him.

How has your ability to maintain a rap career been shaped by being a woman?

I feel like men, usually if they have children, they have somebody that’s taking care of the children versus them being a caretaker. With women, a lot of us are balancing family and that takes priority for many of us. It can slow down your career. It slowed mine down for a period of time, until my child was old enough for me to move a little more clearly and do certain things.

What music are you working on now for yourself?

I put some music out over the summer, me and Crazy DJ Bazarro. We worked on an EP and put some singles out and they were well-received. Chuck D got behind one of them and just went so hard for this particular song, Barbarella.

Sitting back now, thinking about what I wanna do — because I have started and stopped a lot — I have a love and hate relationship with music. It’s like a romantic relationship. There’s been ups and there’s been downs. I wanted to get divorced, walk away, came back, did it again, wanted to leave again.

Stahhr has recently released new music in collaboration with Crazy DJ Bazarro. (Photo: Roy Handy)

Stahhr has recently released new music in collaboration with Crazy DJ Bazarro. (Photo: Roy Handy)

What’s at the base of that?

It’s a love vs hate thing. Like most relationships, the person that you love the most can upset you the most and bring out that anger. It’s still a relationship: there’s anger, there’s passion, there’s creativity, there’s art. I’ve always personified music as a man in my life, like a lot of men refer to hip-hop as a woman. To me, hip-hop is a man. He’s like a lot of the relationships I have had in my personal life. Art imitating life.

How much do concepts such as Right Knowledge influence your music?

Well it influenced everything because when I started writing I was 15. I tapped into Brand Nubian. I had listened to them before but when I started writing I revisited X Clan, Public Enemy, KMD, Brand Nubian, Paris and Ice Cube, who was very militant at that time. So I was always drawn to that, as well as the Wu-Tang [Clan] when they were dealing with the Nation of Gods and Earths information. Most of the music I was drawn to had that aspect of Right Knowledge to it.

I started studying with Dr [Malachi] York in 1996, which was another thing that DOOM and I had in common, because he was a part of the Ansar community in the late ’80s and ’90s. We bonded over that as well. Matter of fact, we attended Dr [Malachi] York’s final class before the compound in Eatonton was raided. Me and DOOM drove down there together. It’s like: wow, we went to Pops’ last class together. Who else can say that? Nobody. We bonded more personally than musically, but the personal bond is what helped with the music. That made it all come together.

Which women were influential in terms of your grounding in hip-hop?

I was influenced by both men and women, but for the sake of the argument MC Lyte, Queen Latifah, Monie Love, Ladybug Mecca, Bahamadia, The Lady of Rage, Rah Digga, Lil’ Kim. I was very empowered. In the 90s and 80s, we had so many women [who] were rhyming. It was beautiful and there were so many different styles and approaches — now everything is homogenous.

For more on Stahhr’s music, visit stahhr.bandcamp.com