Freestyle pantsula dancers in Soweto, Johannesburg, 2016. (Photo: Chris Saunders)

The history of the jol, of dancing after dark, of seeking pleasure amid the desolation of the everyday, is a story of ephemeral places as much as it is about evolving sonic tastes. Who remembers Teasers, an early haven for hip-hop in 1980s Cape Town that shaped the career of Ready D, or Tiles in 1960s Durban, where a young Syd Kitchen was entranced by the strobe lights and psychedelic vibe?

Club names like Jacqueline’s, a high-concept Pretoria discotheque that is central to the early biography of DJ Christos Katsaitis, or Orlando’s Pelican, a place of “clevers, socialites, wannabes and hangers-on”, to quote journalist ZB Molefe from his 2004 obituary for club owner Lucky Michaels, are wormholes to enraptured memories.

Place matters in thinking about nightclubbing in South Africa. Not generic space, but the specificity of the night-time world located beyond the threshold of a door attached to a verifiable street address. In the main, these habitats, so essential to pleasure, often go unrecorded.

During my research for an essay on the history of Joburg’s nightclub venues since the 1950s for the book Ten Cities, I was constantly frustrated by the disappearing act performed by once verifiable places. Newspapers do not run reports on mass assemblies of people exercising their right to dance. The record of pleasure is consequently unofficial and dispersed.

Although some spaces, like Hillbrow’s Chelsea Hotel, managed by former Olympic swimmer Herbert Scheubmayr and Woodstock attendee Dave Marks, are easy enough to locate, others live on in the folklore of bright musical careers.

In 1963, the Blue Notes, a hip jazz sextet on the edge of big things, took up a residency at the Downbeat, a jazz venue near the Chelsea Hotel in Catherine Street. In the early 1960s jazz was an enraptured dance music, and its fans a menace to white bourgeois society.

“Hillbrow and Berea, which were once fashionable residential suburbs, have now become a favourite field of activity for bebop addicts, brazen jazz hounds and bar-smashing youths,” wrote psychiatrist Louis Franklin Freed in his book Crime in South Africa (1963).

Despite the mythology that has grown up around the Blue Notes, who transformed into an important free jazz band in Europe after they went into exile in 1964, their stay in Hillbrow was unremarkable. Downbeat drew a predominantly white audience, although black patrons were not unheard of.

The Jazzomolos: Jacob “Mzala” Lepers (bass), Sol “Beegeepee” Klaaste (piano) and Benni “Gwigwi” Mrwebi (alto sax), Johannesburg, 1953. (Photo: Jürgen Schadeberg)

The Jazzomolos: Jacob “Mzala” Lepers (bass), Sol “Beegeepee” Klaaste (piano) and Benni “Gwigwi” Mrwebi (alto sax), Johannesburg, 1953. (Photo: Jürgen Schadeberg)

“It was never really full, and was struggling to survive, with the guys playing there about three times a week,” recalled jazz photographer Basil Breakey in an interview appearing in Beyond the Blues (1997). “Downbeat never really made money. The music was very avant-garde … It was not just entertaining stuff, it was very expressive, very expressionistic, reflected the society at the time.” The venue lasted six months.

The perishable nature of nightclub venues is easy enough to understand. Nightclubs are parasitic. They rely on fashion as much as define it. Taste is fungible. There are always new clubs with new sounds catering to a new “it” set. Pleasure is mobile, not sedentary.

Many of the ideas that still define the restless nature and impermanent life of Joburg’s nightclub spaces were settled in the post-war years. In 1956, Lewis Nkosi, a 20-year-old journalist who had just quit his job at the Durban-based Zulu-language newspaper Ilanga lase Natal (The Natal Sun), arrived in Johannesburg to begin work at Drum, a new Anglophone African current affairs magazine.

Nkosi, whose name still looms large in South African arts and letters, even after his death in 2010, immediately became part of the city’s jazz-infused high life. He made friends and socialised with the cosmopolitan intellectuals that staffed Drum, among them Ezekiel “Es’kia” Mphahlele, Todd Matshikiza, Bessie Head and Can Themba.

In a 1986 interview, Nadine Gordimer recalled Themba arriving at her home one day with “a rather snooty-looking young man” — Nkosi, who cultivated an indifferent air in Gordimer’s patrician home.

“Any music in this place?” he asked Gordimer.

“Yes,” she said, gesturing to some vinyl records.

“This is not music,” sniffed Nkosi. “It’s all classical!”

Nkosi was a man apart. At the time of his visit, he lived in Themba’s one-roomed house — dubbed the “House of Truth” — in Sophiatown. Invoking Sophiatown in a 1972 essay, Nkosi described the mixed-race residential neighbourhood northwest of the central city as a “folk institution”. It was, Nkosi elaborated, a place composed of “extravagant folk heroes and heroines, shebeens and shebeen queens, singers, nice-time girls”.

A Drum magazine cover from February, 1955. (Photo: Jürgen Schadeberg)

A Drum magazine cover from February, 1955. (Photo: Jürgen Schadeberg)Nkosi arrived in Johannesburg during a remarkable flaring of black urban culture, a time of the “the new African cut adrift from the tribal reserve — urbanised, eager, fast-talking and brash”, as he would later write. Music and dance — and in its own way alcohol too — was central to the character of this cultural renaissance.

Sophiatown, with its “swarming, cacophonous, strutting, brawling, vibrating life,” as Themba described it, was the epicentre of this scene.

“There weren’t really any clubs,” recalled photographer Jürgen Schadeberg in an interview. The dance venues, he said, were very makeshift — an informality and precarity that persist as features of Joburg’s dance halls and drinking establishments. “There was this place, which was originally an old corner shop,” continued Schadeberg. “The windows were covered with cardboard. They made a little stage with old pieces of wood. This is where people went and danced.”

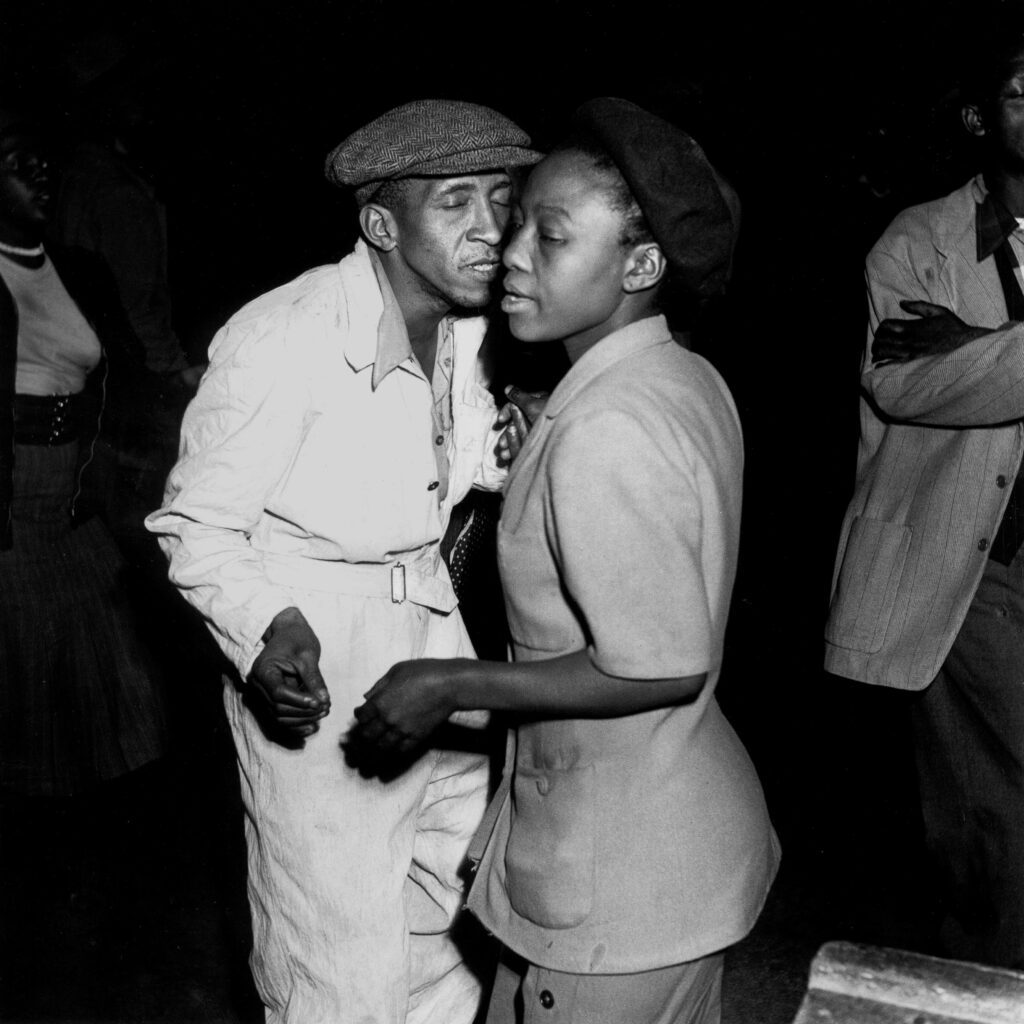

One night in 1955 Schadeberg walked into this Sophiatown dancehall with his Rolleiflex camera. He was 24 and had a head full of jazz. Amid the melee of bodies moving around the room that night, he spotted one particular couple dancing. The photograph he took offers a valuable clue about the character of dance and revelry during the formative years of high apartheid.

The female subject wears a beret and twinset, her male partner a flat-cap and beige boiler suit. The couple’s manner distantly echoes the smartly dressed couple (actually a brother and sister) dancing barefoot in one of Malian photographer Malick Sidibé’s many photos of Bamako’s post-independence joie de vivre. But in Schadeberg’s photo, taken a decade earlier than Sidibe’s, the couple’s expressions are less joyous, more concentrated.

The two dancers’ eyes are pinched shut. I read this not singularly as a gesture of rapture but also refusal: they are rejecting the political savagery disassembling their neighbourhood, a brutality happening more or less in tandem with the experimental modernism unfolding elsewhere on the continent.

Photography, more so than written journalism, is important to anyone interested in the history of pleasure, of dance and dance venues in South Africa. Photography offers an important means to visualise, as much as imagine, the topsy-turvy world Nkosi arrived upon in 1956.

Township Shuffle. Sophiatown, 1955. This image offers a valuable clue about the character of dance and revelry during the formative years of high apartheid. (Photo: Jürgen Schadeberg)

Township Shuffle. Sophiatown, 1955. This image offers a valuable clue about the character of dance and revelry during the formative years of high apartheid. (Photo: Jürgen Schadeberg)

On the one hand, the late 1950s was a period of intense civic agitation. News photos from the period show men and women of all races gathered in huddles in public places conversing, often amiably. The locus of struggle was typically the formal city, in particular its courtrooms, more often than not the great staircases and public areas that typify these places of the law. The 1960 Sharpeville massacre and jailing of the country’s anti-apartheid political leadership four years later, both well-known events, however, marked a shift towards a more physically balkanised and repressive society.

But, and this is important to recognise, for all the repression and violence that marked the apartheid years there was also music and dance. Pleasure is a makeshift ideology that embraces refusal.

South African writers have been actively digging in the muck of history to excavate new stories about the old country, but still there is no exhaustive account of Jo’burg’s nightclubs and dance venues.There is no defining study of the habits of this city’s obsession with music and dance, also drinking and drugging, after dark.

The evolution of musical taste, from analogue instruments to machine made, is well known. The role of Simon Spiller’s 40 Watt Club at Joubert Park, of Eric Kirsten and Preston van Wyk’s Fourth World, whose ethos was millennial, druggy and optimistically nonracial, remains a thing of oral historians, of aging red-eyed ravers who remember when doof-doof-doof replaced the twang of guitars and screech of saxophone.

Jo’burg, more than any other city, deserves such committed pause and archaeological work. Its dance halls and clubbing spaces offer a way to read the city’s history at its most convivial and joyous, as well as its most embittered and unstable. The night is a time of diversionary pleasures, of respite and pause, but not release from the city’s acquisitive and mercantile logic.

Behind the filigree of pleasure offered by music, dance, alcohol and other more exotic poisons remains the sobriety of a city characterised by exploitation, oppression, alienation, violence and enforced strangeness. Nkosi knew this.

For Nkosi, Johannesburg was a desert, a far-flung metropolis cut off from the Western cultures it desperately aped. Underlying the habits and routines of post-war Johannesburg’s inhabitants, Nkosi intuited “an appalling loneliness and desolation”.

Writing in his 1965 essay Home and Exile, he said these hallmarks of life in the big smoke made it “so desperately important and frightfully necessary for its citizens to move fast, to live very intensely, to live harshly and vividly” — in short, to dance.

Ten Cities (Spector Books/Goethe-Institut), a book on clubbing in Nairobi, Cairo, Kyiv, Johannesburg, Naples, Berlin, Luanda, Lagos, Bristol and Lisbon between 1960 and March 2020, is edited by Johannes Hossfeld Etyang, Joyce Nyairo and Florian Sievers. This extract, on the ephemerality of place and the impact of apartheid on Johannesburg’s clubbing landscape, is the fifth in a series of 10 weekly excerpts from the book.