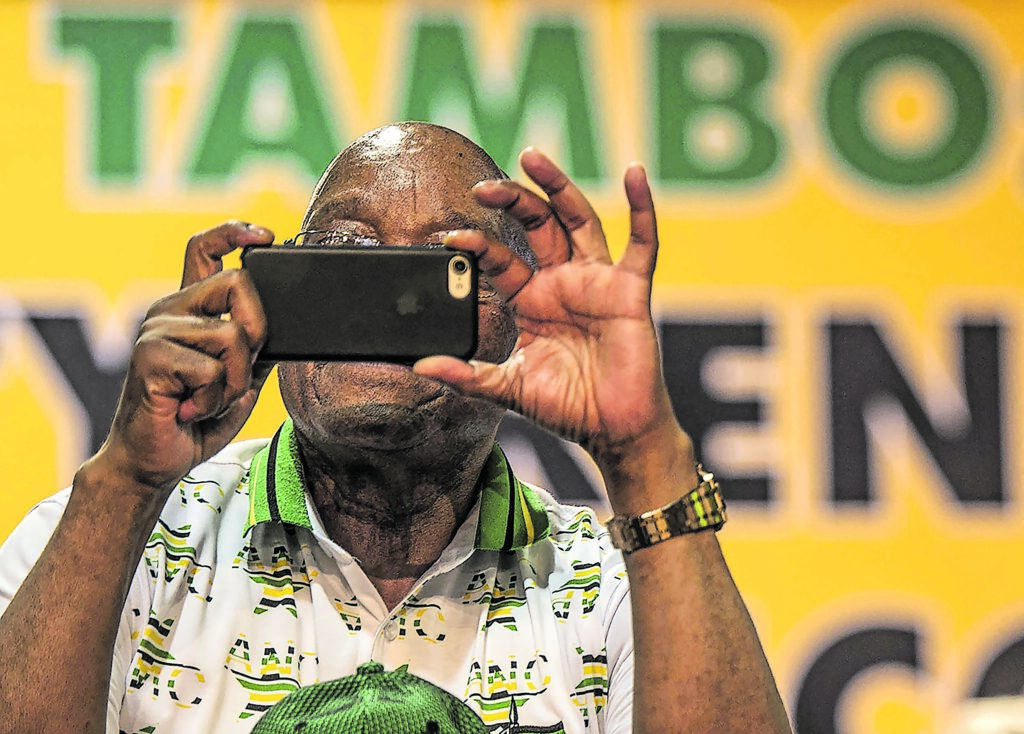

One-way flow: From Nelson Mandela to Thabo Mbeki, Jacob Zuma and Cyril Ramaphosa (above), there has never been a standard of high engagement between the press and the president in South Africa.

Thanks to the Covid-19 pandemic a new concept has been introduced into our lives: the family meeting. Every few weeks, President Cyril Ramaphosa appears on our television screens to bring us up to date on the status of the nation and the regulations that will be amended shortly.

There is nothing novel about a presidential address, but the regularity and significance of the briefings are unprecedented.

Their nature is also distinctly one-sided.

The head of the household talks and the rest of us listen. When it ends, we go our separate ways and are expected to do as we are told. No back chat, no questions.

It is a format that is beginning to perturb a great number of people, and has highlighted some of the shortcomings in how we interact with our government executive. Should the president not be subject to interrogation? Is it not our democratic right to demand the reasoning behind major policy decisions?

These are unparalleled times but, in truth, South Africa has never enjoyed a forum in which its journalists regularly and meaningfully engage with our president.

The status quo

It’s easy to understand why many people in the press (and the public) feel irked about the current dispensation. The Covid-19 pandemic has presented the biggest challenge to humanity in most of our lifetimes. It is a novel virus and, as such, the science and information around it is fluid. From day one, decisions have had to be made on incomplete evidence, with a high degree of critical interpretation.

Demonstrators at a Right to Know protest against the proposed media appeals tribunal in 2011. (Photo by Gallo Images/Foto24/Alet Pretorius)

Demonstrators at a Right to Know protest against the proposed media appeals tribunal in 2011. (Photo by Gallo Images/Foto24/Alet Pretorius)

The briefings of the National Coronavirus Command Council (NCCC) notwithstanding, much of the nation’s approach over the past year-and-a-half has been relayed through one man. There is rarely a rationale provided, or space for debate. The president himself, most likely, is merely repeating what has been decided by the NCCC and then processed by scrambling speech writers with a limited amount of time.

As the Mail & Guardian wrote in its editorial at the beginning of July: “Like his predecessor, Jacob Zuma, he [Ramaphosa] largely governs through poorly crafted statements and speeches from the communications teams, leaving little space for scrutiny by the media.”

The patterns of the family meetings are easily discernible and can be broken down into a simple formula.

- Greetings and platitudes;

- Setting the scene: The latest Covid figures and the outcomes of government efforts;

- Resolutions taken: What new regulations are coming into effect; and

- Appeal to comply: A heartfelt request for all citizens to do their national duty.

The least cynical explanation for this one-way strategy is that it was designed to foster a national feeling of solidarity. By closing off the avenue for rebuttal, dissenting voices are not given an opportunity to rupture the conjured ideal of a nation standing as one to fend off a threat to our way of life.

“The ‘family meetings’ term attempts to create a warm fuzzy feeling,” reasons Glenda Daniels, scholar and author of Fight for Democracy: The ANC and the Media in South Africa. “And, I guess, in some quarters it succeeds; this attempt to create unity for South Africans, cohesion — with the president, ruling party, nationhood, and so forth. Terms which tend to hide chasms, gaps in South Africa’s democracy.

“Some don’t like journalists because they break the falsehoods of the charming national unity, conflation with party, government, state and the people by asking awkward questions — on behalf of democracy and society at large. Or those who have questions,” she adds.

There is also the idea that even, if he did take questions, Ramaphosa would be unable to offer much beyond standard bromides; hamstrung as he is by political and financial constraints.

For instance, Isobel Fyre, director at the Studies in Poverty and Inequality Institute, argues that Ramaphosa’s speeches last year tended to pack more promises of economic relief. When it became clear that he was unable to lasso the national budget, that largesse disappeared — to the point at which he could, arguably, offer nothing of consequence when he addressed the nation during the unrest that followed Zuma’s imprisonment for contempt of court last month.

“Last year the president spoke left and treasury spoke right,” Fyre says. “Now you see the president not promising anything at all; a very robotic announcement without offering any hope. It seems the technocrats have prevailed.”

As exceptional as these times are, it’s worth re-emphasising that, in South Africa, there has never been a standard of high engagement between the press and the president.

Ramaphosa has aimed to sit down with the South African National Editors’ Forum at least once a year since assuming office (through Zoom meetings in the past two years). To many people, however, such mini-conferences are far too irregular to retain any significance.

Legacy of distrust

South Africa’s sitting president may be facing calls to increase his capacity for dialogue, but there is little question that he is a significant improvement in this regard from his obstinate predecessor. It’s an observation neatly encapsulated in the events of the Zondo Commission of Inquiry into State Capture over the past few months.

Although Ramaphosa has, arguably, floundered in terms of his own testimony, he has, at least, demonstrated a willingness to be forthcoming. Zuma, meanwhile, has been happy to retain his contemptuous disposition, even though it has driven him directly behind bars.

It’s an attitude that was familiar during the Zuma presidency. Especially with regards to the media.

Watching you: Former president Jacob Zuma (Photo by Mujahid Safodien/AFP)

Watching you: Former president Jacob Zuma (Photo by Mujahid Safodien/AFP)

Multiple scholars have written about the malaise with which the ruling ANC has interacted with the press. In the immediate years after its election, a tendency emerged to conflate scrutiny with deliberately attempting to derail the revolutionary party now in power. It was a perception fanned by the slow racial transformation of media ownership.

Even Nelson Mandela, who had spoken boldly about the integral role of a free press, “did not always support freedom of the media”, wrote Sue Valentine of the Committee to Protect Journalists in 2014. “In 1996, his criticism, especially of black journalists and editors he viewed as disloyal, set off alarm bells among press freedom advocates. In June 1997, Mandela met members of the South African National Editors’ Forum in a tense stand-off.”

“Mandela charged that black journalists did not write freely because to earn a living they had to ‘please their white editors’. Mandela also complained that editors ‘suppressed’ ANC responses to critical articles.”

This narrative was scooped up by his deputy and later successor, Thabo Mbeki.

“The serious chilling effect Mbeki had on the media was to play the race card,” writes Mark Gevisser in his biography of the former leader. “He went for his critics — black and white — and demonised them, branding black critics ‘Uncle Toms’.”

But it was not until Zuma’s tenure that the government attempted to implement systematic, pernicious legislation that threatened to curb media freedom.

Following on from discussions during its 2007 Polokwane conference, the ANC produced a policy document in 2010 that sought to establish a media appeals tribunal. The premise behind the tribunal was that it was nonsensical to have the media serving as its own watchdog. An external body, accountable to parliament, would need to be established to protect the rights and dignity of those who found themselves in the headlines.

Extracts of the discourse that followed demonstrate just how severely the Zuma-led ANC distrusted the media.

“If you have to go to prison, let it be,” said then-spokesperson Jackson Mthembu of the consequences of the tribunal. “If you have to pay millions for defamation, let it be. If journalists have to be fired because they don’t contribute to the South Africa we want, let it be.”

Fikile Mbalula insisted the press “cannot be a player and a referee”. He was echoed by then ANC Youth League president Julius Malema: “These people are dangerous. They write gossip and present it as facts.| (That same year Malema would achieve international infamy after he chucked a BBC journalist out of a press conference for “misbehaving”. “This is not a newsroom, this is a revolutionary house,” he barked, before calling on security to remove the bemused offender.)

Ultimately, the plan did not come to fruition, with ANC leaders begrudgingly admitting that the media would have to sort itself out after all. The lines of division, however, could not have been more clearly marked.

A new dawn

To the relief of many people, the draconian measures threatened by the tribunal are now a distant memory. Should both sides display a willingness, there is undeniably scope for the president to interact more with the fourth estate. Sharing a healthy back and forth while elucidating his ideas could only serve to strengthen our democracy.

What form that engagement might take is an interesting discussion.

Given the global fascination with US politics, the White House news conferences are an example many people might be familiar with. It’s not a perfect comparison: Americans directly elect their president, unlike in South Africa’s parliamentary system. But the sheer regularity with which their leader finds himself at the end of potentially pointed questions is precedent not easily dismissed.

The tradition began back in 1923 under Calvin Coolidge, when members of the swelling press ranks were allowed to submit questions in writing — not all of which would be answered. By the Dwight Eisenhower administration in 1953, this had evolved into the conferences the country enjoys today.

Just how many times the sitting president found themselves in front of cameras and microphones was influenced by their own proclivities and world events at the time. Ronald Reagan had a famously low number of 46 over eight years, whereas Barack Obama held 163, including joint conferences, over the same period.

Open to questions: Former US president Donald Trump faced reporters 36 times from 2020 to 2021. (Photo by Brendan Smialowski / AFP)

Open to questions: Former US president Donald Trump faced reporters 36 times from 2020 to 2021. (Photo by Brendan Smialowski / AFP)

Donald Trump was much chided for his interactions with the press — often preferring to communicate through Twitter and regularly insulting journalists. But from 2020 to 2021 he faced reporters 36 times.

The practice is as much about culture as it is policy: in many major newsrooms the role of White House correspondent is one of the most coveted for many political journalists.

As is the criticism in South Africa, the past year of the pandemic in particular would seem to necessitate a greater need for transparency and constructive conversation between world leaders and their respective media.

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson is another leader who has held regular press briefings and conferences in recent times. Each one is transcribed and then uploaded online for public record — including all interactions with journalists. Having developed a penchant for pressers, Johnson has vowed to follow the White House model; a decision manifested into a new £2.6-million briefing room (not without its own controversies). Johnson reasoned: “People have liked more direct, detailed information from the government about what is going on.”

Neighbouring First Minister of Scotland Nicola Sturgeon and New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern are two more examples of leaders who have recently been recognised for answering questions forthrightly when presenting new Covid-19 lockdown restrictions or vaccine approaches.

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson has vowed to follow the White House model, saying: ‘People have liked more direct, detailed information from the government about what is going on.’ (Photo by Leon Neal – WPA Pool/Getty Images)

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson has vowed to follow the White House model, saying: ‘People have liked more direct, detailed information from the government about what is going on.’ (Photo by Leon Neal – WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Of course, mimicking any other country, specifically those of the developed Western world, is not an elegant solution for South Africa. We can, however, take lessons from instances in which we see democracy deepened through routine and rigorous discussion.

Only by embracing debate will we avoid stumbling into the bitter cycle of recriminations we witnessed a decade ago when the media appeals tribunal was first mooted — a trap from which we might not be so lucky to escape next time round.