As a member of Scienz of Life and as a solo artist, John Robinson worked with DOOM for years, building a strong friendship with him during their time in Atlanta. (Photo courtesy of John Robinson)

As a member of the New Jersey-based hip-hop group Scienz of Life, Sci (who was later to be known as John Robinson, his birth name), quickly established a reputation as a top-quality emcee, with an instantly recognisable voice and an ability to make dense, philosophical concepts digestible for the average listener. In this way, he was the opposite to his brother ID 4 Windz, who often tended towards wilful, eloquent abstraction. This approach, combined with their elemental, sometimes melodic but always atmospheric beats, made them a mainstay in an American underground hip-hop scene that grew increasingly independent as the nineties gave way to the 2000s.

In this interview, Robinson goes into detail about meeting DOOM (who passed away in October last year), first in the late nineties in New York and then later in Atlanta. DOOM had moved to Atlanta around the turn of the century, just before Scienz of Life, and began working in earnest on future releases, some under the (MF) DOOM persona, as well as others in collaboration with artists he was already associated with or met on his journey. The fruits of this labour can be seen in the phenomenal production of the album Take Me To Your Leader (released as King Geedorah in 2003) and others, such as Vaudeville Villain, released as Viktor Vaughn.

Scienz of Life later moved to Atlanta to set up shop in the South, where they worked with former Company Flow member Bigg Jus, as artists and as part of the team driving Jus’ label Sub Verse Music. Sub Verse was an underground fixture that had mastered the independent system of releasing music.

Robinson speaks at length about observing and working with DOOM, establishing a bond that developed into something of a brotherhood. Their collaborative album Who Is This Man? was released on Project Mooncircle in 2008.

I don’t know if there’s a beginning in this story. Do you remember the first time you crossed paths?

I’m gonna mention the indirect cross and then the direct. The indirect is spiritual. The indirect is KMD [his first group with his brother Subroc and Onyx], Mr Hood [their first album] and not just the album but the visuals: seeing young black men being cool and having a sense of self, but also being very intelligent and that being the cool part of it. “I got knowledge of myself. I read books. I’m into girls but, yeah, I care about how I look. I’m into self care.” That whole era was something that my group, Scienz of Life, was very attracted to. So that was the beginning for us. We saw that. We loved those brothers like family before we met them. Easily.

I never got to meet Subroc (Rest in Power), but the initial meeting with DOOM was through working with Bobbito Garcia (Shout out to Bobbito!), on Fondle ’Em Records. We were at Bobbito’s store on the lower east side of Manhattan, this is circa 1998.

It was [around the time of] the second record we released with the label. We were just there handling some biz. Bobbito was like, “Yo. Have y’all ever meet DOOM before?” We were like, “Nah.” He was like, “Well, he just left. He might still be outside trying to catch a cab or something.” So we run outside. We see DOOM way up the street. We run up the street screaming his name. He probably thought we were crazy, man. But we catch him right before he is jumping into a taxi and give him his props. We let him know who we were and that we just wanted to meet him and let him know, “Yo, we working with Bob too.”

Scienz of Life (left to right) Lil Sci (John Robinson), Inspector Willabee and I.D. 4 Windz (Invizible Handz) in New Brunswick, New Jersey in 2018. This is the last photo of all three Scienz Of Life members before the passing of Inspector Willabee in 2019. (Image courtesy of John Robinson)

Scienz of Life (left to right) Lil Sci (John Robinson), Inspector Willabee and I.D. 4 Windz (Invizible Handz) in New Brunswick, New Jersey in 2018. This is the last photo of all three Scienz Of Life members before the passing of Inspector Willabee in 2019. (Image courtesy of John Robinson)

He wasn’t super familiar with us at the time, but he definitely had heard of us. So it wasn’t until about a year after that first meeting that we did our first show in Atlanta. We got down to ATL. It was [a] Scienz of Life and Bigg Jus [show] at this venue, MJQ. We get there and DOOM is standing in front of the venue, right before soundcheck. We like, “Yo what you doing here?” He’s like, “Yo, I live out here now.” And we got to really chop it up then and meet for real, for real. And DOOM and Jus knew each other already through Mr Len. I wanna say after that, maybe a year after that, we all moved to Atlanta as well and that’s when we really got to connect from the year 2000: really being in the studio together, working, hanging out, breaking bread and things like that.

What made you guys follow DOOM to Atlanta?

We didn’t follow DOOM. We didn’t know he was there. We moved to Atlanta because at the time we were working with Bigg Jus. And this is gems right here. We were working with Bigg Jus. (Shout out to Bigg Jus, man. That’s another scientist for all you who don’t know man. That’s a guy who has a lot of answers on the infrastructure of how the music works as an independent artist, et cetera. He was telling us futuristic gems in the late ’90s, but I digress.)

Bigg Jus had this idea. He’s like, “Look fellas, we got to realise we are in the north, we’re in the northeast, it’s dope; we’ve been in New York and the Tri-State area, pretty much, from the start of our careers until now. We have this label situation now: what if we move to the southeast because, guess what?, the southeast is untouched; Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Florida, Georgia, New Orleans, et cetera — untouched ground and they all know who Scienz of Life and the Lyricist Lounge is. They all know who Stretch and Bob is, they know the cloth we are cut from but nobody goes there. We could set up in Atlanta and just start championing that area and being there.” And that’s what we did. We created a satellite office for the label and Scienz of Life.

In my opinion, it was one of the most innovative, independent record deals of its kind at that time. Because, in exchange for our living expenses, access to a 15-passenger tour van, expense gas cards, et cetera — just all of these intricate resources you’d need as an independent artist — we were working for the label but we were doing things like retail stops. If we stopping at a record store to promote our music, we would also promote Micranots and Blackalicious and Rubberoom and other artists that were on the label. We were doing street team work. I was doing a lot of the radio DJ calling. At one time I knew every retail buyer of every major record store in every city in America by first name, and that was [from] Bigg Jus saying, “Yo, Sci. You got the most distinct voice, if they hear you call and they know it’s you, they’re gonna order more records, and they are gonna feel more personable about this connection.” We really broke it down to a science.

When we moved to Atlanta, we rocked it like a nine to five. Every day I’d scream and wake everybody up, “Yo, it’s time for your daily Afrobics.” And what that was was whatever we meant it to be: if we played basketball that morning, if we lifted weights, if we took a jog, whatever.

We’d come back to the [3500 square foot] loft and shower up, break bread together, have a meeting and break off into our sections. Like I said, I was on the phone. I was on the website design. Back then I was learning Microsoft Front page and Dreamweaver, [Scienz of Life member] Inspector Willabee (Rest in Power), was on the Photoshop and graphic design work. ID 4 Windz was on the ASR X and the ASR 10 and on the production tip. Then we got an MPC and he was really focused on that on the daily. By three to four o’clock, Bigg Jus came through and we rehearsed like a band, but not traditional band style.

[We had] drum machines, hand drums, kalimbas and just different vibes. We basically used that time as currency to learn how to do the things we knew we’d have to do.

During that time, too, DOOM would come through. I just told this story the other day: the I Hear Voices song. DOOM came through to the loft to kind of get out the crib. He had his MPC and he sat in the corner with headphones on for about three hours just chopping up this beat. And when he played the beat for us, we were like, “Oh, this is dope.” (At the time it was a bonus song for the re-release of the [Operation]Doomsday album on Sub Verse Music.) We were blown away, but we were like, “It must be the bonus instrumental. There is no way he is gonna rhyme on that, that’s way too fast.” And then two days later he comes back with the song on CD and he pushes play and he is rhyming on the beat — perfectly riding every melody and nuance and we just like, “Holy shit … this dude is incredible.” Those were the moments when we really recognised his genius. It’s funny, he was so humble. He didn’t necessarily poke his chest out and say, “I’m the illest.” At times he seemed unsure about what he was playing us and we looked at it and were like, “Yo, this is amazing.”

He’d always tell us that Subroc was his hero when it came to beatmaking, particularly. He said after Subroc transitioned, he felt it was his duty to get good at making beats. This is around the time he started really going in and finding his process on the MPC. That was the Atlanta movement. It just so happened that when we planned the move — I don’t wanna say we didn’t know DOOM was there because we saw him the year before — but when we made the move it wasn’t to link with DOOM, it was more, for lack of a better expression, to conquer that part of the country.

That’s when we realised that Atlanta is a hub for people from California, people from Florida, people from Chicago, New York, Philly. It was just a melting pot of all these different people from different cities that gave it an interesting vibe when it came to the music scene, the art scene, or the entertainment scene in general. But then the culture, too — the different creative businesses that were happening. It was very inspiring and I think we moved there at a perfect time in our creative development. It helped us grow. I wouldn’t change any of those times for anything. It was such a powerful and necessary time for allowing us to still operate the way we know how today.

Can I backtrack a little bit. I want to come back to Atlanta but I want to ask you this: In the mid- to late ’90s, do you know about what it took for him to be mentally prepared to remerge after the demise of KMD, with his brother transitioning and him having to refigure his career?

I won’t speak much on it because I wasn’t there. I didn’t know DOOM yet. But what I do know is there were people around him that helped that process. There were people like Kurious, MF Grimm, people like Stretch and Bobbito, Lord Sear who were just helping get the music done. The only thing I can say I know is, before Operation Doomsday dropped, Jus and I were in Manhattan doing some business and we ran into DOOM on the street and he was telling us about a session and how he was doing. He mentioned the piece of equipment he recorded the album on. It was the Roland 880, this digital piece of equipment. It was portable but you could record in full digital quality anywhere. He was super excited about it: how much he was able to get done and how quickly. I ain’t gon’ front, a lightbulb went off. I wrote it down and I started researching. We bought the model after that, which was the 1680, and that’s kind of what we used until probably Scienz of Life’s second album.

I just saw that he was excited to have this music, and he knew that people — at least based on the 12-inch vinyls that were out already: the Gas Drawls, the Hey, Dead Bent — peops was feelin’ the vibe.

I learned later that he didn’t know how big this thing was going to be, but he just felt good again about creating music that the people around him were excited about. That’s what it was for him. “Yo, does the crew feel it? Are cats vibing that’s right around me? Do I feel that energy?” I know he was around some dope people. It definitely helped him re-emerge and helped him get the work done.

John Robinson (Lil Sci), I.D. 4 Windz (Invizible Handz) and the late Inspector Willabee in Atlanta, Georgia, 2002. (Image courtesy of John Robinson)

John Robinson (Lil Sci), I.D. 4 Windz (Invizible Handz) and the late Inspector Willabee in Atlanta, Georgia, 2002. (Image courtesy of John Robinson)

When a lot of people look at his career, they kind of speak about the early 2000s as this whole flurry of releases. But, as you describe it, that kind of took a couple of years to bubble. What was the mindset he was in in Atlanta? I’m guessing that’s when the plans for all of these releases were really being cooked up.

That’s when we wound up being labelmates again. I remember we were at the loft chilling and we had a conversation that led to DOOM also re-releasing Operation Doomsday on Sub Verse and re-releasing Black Bastards on the same label. Jus was heading up the label with some silent investors as well, but he was the front guy making the decisions. (Shout out to Fiona Bloom, she was a part of the label as well.) It was that moment, I think. Him being there, family styled out but also having his home studio and his headquarters in a different space. We’re in ATL, but we’re not in the city. We’re on the outskirts. It’s nature. It’s quiet. It’s a different life. It’s kind of laid back. You can go outside in the backyard. You can think. It’s pretty warm there. It was a lot different from New York for all of us.

He was in a zone there, definitely. He was on the Special Herbs beats, et cetera. All that stuff was being created during that time, right there in ATL. I feel like he was really on the study of his beat journey. He really put the hours in. You’d go to DOOM’s lab at any moment and he’s up late and the beats are rolling. He’s searching for those perfect stand-out, amazing loops. The drums. There was always a lesson with DOOM. He was always on. Always learning something. Always sharing something.

But then again, you live in a place where no one can just go around the corner and knock on your door. Nah. You gotta call me and plan when you’re coming here. And even where we [Scienz of Life] lived, we lived like 40 minutes outside the city. When we first got there it would freak us out how we’d have to drive on the highway; the 85 South from Atlanta going back home. At a certain point on the highway, you rolled down the window and you heard no noise. It was like, “Whoa!” We never heard that much quiet in our lives. There was always a police siren; there was always a car. You know, New York: it’s the city that never sleeps; it’s for real.

We appreciated it. We talk about it all the time, how much it lent to our creative selves, just being there … There was a lot of culture, too. Because Atlanta is definitely a place where black people run the spot, man. We out there, heavy and really.

One of the gems I picked up on, which was probably recorded around that time, is the song Next Levels. I can’t overstate how beautiful a piece of music it is, both sonically and lyrically. Do you remember how that became a song with the three emcees on it, the DOOM beat and how that came together?

Yeah man, I’ll never forget that. Actually, at this time, I was transitioning, moving apartments, and I lived with DOOM for about a month. He was working on King Geedorah, the album. It was a production album. It wasn’t really from the standpoint of DOOM rapping. Even though he is on a couple songs out there, the whole concept was him getting “different emcees that I respect and I feel on this record”.

Actually, it took a couple of sessions to complete that beat because he had the drums down for a while and he was looking for the right type of thing to lay on those drums. When he got that down man, we must have listened to that beat for five hours straight, without even talking. We said, “DOOM, technically this could just loop and be good and break a little part.” He was like, “Nah, I gotta do some little things. I don’t know what.” He was trying to decide where the break was gonna be and then we decided not to make it traditional in the sense where the horn comes in on every hook. We decided we just gonna format the beat in a way where it feels like we’re rocking on jazz vibes with musicians and we’re going in. Me and ID, my brother, we rocked on it first and recorded it. The next day Stahhr came through and then Stacey Epps laid her vocals on last. She’s kind of like on the background vocals vibe.

It’s a very special song. It really can improve one’s state of mind from just taking in the words. What sort of information were y’all dealing with?

Like I said, I’m all about the spirit. We were into a lot of different things, and we were reading books from Five Percent lessons to Dr [Malachi] York books, to Noble Drew Ali, the Koran Circle Seven, to passages from people like Duse Ali and Shaikh Daoud. It was a journey that we were on and it was more like, “Yo, we gotta find who we are. We’re in the wilderness of North America. Are we natives of this land and part of the indigenous folks that were here already that they don’t tell us about? Are we from the continent? Were we part of the capture and brought here? How do we connect these dots?”

And that’s what the science of life is about. You are always learning. There is always more to know about life. The science of life is mindfulness and openness, and being open enough to know that you don’t know it all. There’s always more, but also doing the knowledge to the masters that came before us and say, “Yo, there’s cats who died to give us this information, who knew that they wouldn’t see what they wanted to see happen in their lifetimes, but they were selfless enough to push forward with what they had heeded so that the gems get to the next generation.” So how could we dare know this and ignore these blueprints? We basically took pride in that. And then DOOM, with his early spirituality with KMD and the Ansar community. All of that was connected. We were easily able to build on that level. Then there was Stahhr. We met Stahhr in 1997 on that land that Dr York had in Eatonton, Georgia. She was in a cypher freestyling and she became my sister from that point until today. So yeah, we all spoke the same language, that language was black spirituality, culture, upliftment, empowerment.

Be aware, be focused, be open. I think that was the overlying connection for all of us, where it was knowledge of self — that’s what glued it together. The fact that we all knew that we were doing what we did for a greater cause than just getting props and looking cool. It was to leave something here that someone could literally take and feed from. When I listen to it, I can’t believe that I was that young and even saying things like that. That’s what I was saying at that moment: “Take your life to next level or remain no more.” It blows my mind, but then also, I’m someone who definitely gives thanks and I’m very close to ancestry and that power. I know that I have written things that are channelled to me.

I don’t take it for granted, ever.

The way DOOM was able to channel that information, it was like he seems to have distilled it carefully and deliberately, whereas with Scienz of Life, the lessons came a little to the forefront and more directly.

Agreed. I think that was the cleverness of his reemergence as MF DOOM from Zev Love X. Because if you think about it, Zev Love X was all about that. He is the knowledge-of-self guy; he is the scientist who could drop gems and, you know, bring it in that way, forefront, like you mentioned. DOOM is the guy who said, “You know what, I’m gonna take all these gems and break them down, decompose them and turn them into honey, into these clever funny bars that might make you laugh, that might make you think, “aah, this is funny, or nerdy, or comes off quirky.” But, when you really sit back and think, you’re like, “Damn, that’s high science. This dude, he might be joking around, but he just taught me how to build a pyramid.” Not literally saying that, but he always had this way of disguising the messages in a way where it’s like, “I’m gonna give you what you want, until you want what I really have to give you. But guess what, what I really have to give you is already baked in there. You just gotta keep listening and it will unfold.”

And maybe those who are supposed to get that part of it will get it, but then those who just get the light-hearted part, that’s the message for you. And that’s what I love about the message of DOOM. There’s so many layers to it. There’s people who clearly see all of it and say, “Ah man, this guy’s a genius.” And then there’s other people who look at it as just, “The funny rapper who says a lot of clever lines.” But they don’t get to see the other side. There’s the advanced mental part and I think you need to be there to get that part.

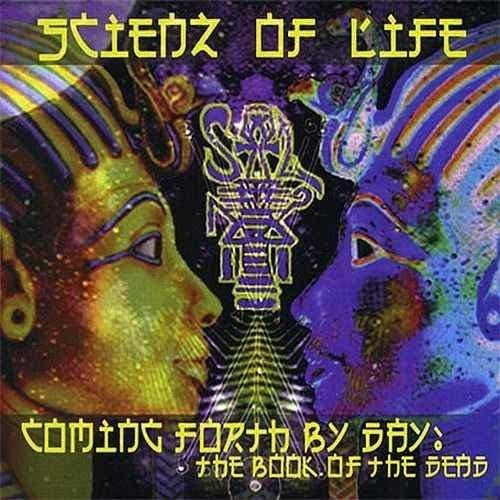

The cover artwork of Scienz of Life’s landmark album Coming Forth By Day

The cover artwork of Scienz of Life’s landmark album Coming Forth By Day

For us, we transformed to that. He was one of our inspirations to do that. If you listen to Scienz of Life’s first album [Coming Forth By Day] and listen to the second album [Project Overground: The Scienz Experiment]… in the first album, we weren’t in Atlanta yet. We moved there while that album was out, right after it dropped. Second album, we were there, taking in all that, and learning more and getting more refined in our process, how we put the messages less in the forefront and more in the intention; where we didn’t have to say every literal thing we wanted you to feel.

Instead of talking about payola and conspiracy theories with the radio, we just say, “They don’t play them songs no more.” People would be like, “Yeah I know what you mean, that’s true.” But it’s like, it’s more laymans’ terms. It’s more jazzy vibes than before. We were getting into soulful vibes and wanting women to connect with it more. We knew that you cannot build a civilisation without women, and we knew that in underground hip-hop, it was more notable to have a show full of dudes. It was like, “Nah. Scienz of Life, we ain’t doing that. We’re bringing the sisters to the forefront.” We’re bringing them on stage, too, so that the women could come in and it was always a balance. That was what we learnt from DOOM.

Other mentors and spiritual advisors would always tell us, “We love what you’re doing and all that knowledge you are dropping but, technically, you’re gonna build a following of only people who understand that terminology. What about the people who need to hear the messages that y’all are bringing? How you gonna reach them?” And it made us want to universify the message and make it something that was less direct, and make it, “Wow, I can enjoy this, and before I know it, I’m learning things.” And that became, pretty much, my formula to this day.

Part two of the interview with John Robinson can be read here: